The Enchanted Ring of Budapest: Inside the Capital Circus of Budapest

The Capital Circus of Budapest is one of those places where you feel the atmosphere change the moment you step in. The lights are softer, the air is charged with anticipation, and even before the first drumroll, you sense that this is much more than a children’s show. It is the only permanent “stone circus” in Central Europe, a year‑round cultural landmark in Városliget, the City Park, and a living archive of over 130 years of Hungarian and international circus history.

A City Park Turned Circus Wonderland

The story of the Budapest circus is inseparable from Városliget. At the end of the 18th century, this area was still a marshy, sandy “city forest” on the outskirts of Pest. As it was gradually transformed into a landscaped public park, it became the city’s playground, filled with ice-skating ponds, racetracks, small theatres and travelling performers who entertained families coming out for fresh air and fun.

In 1889, this lively atmosphere took a decisive turn when Ede (Eduard) Wulff, a German–Dutch circus director, opened the first permanent circus building inside the Zoo’s grounds. The structure was pioneering for its time: instead of flammable wooden walls and canvas, Wulff insisted on a modular iron frame covered with tin, with iron seating structures and backstage spaces. Safety was a priority in an era when circus fires were a real danger across Europe, and Budapest immediately placed itself at the forefront of modern circus architecture.

Audiences loved the combination of innovation and spectacle. The building could seat more than two thousand spectators, and inside, they discovered something extraordinary: a ring that could transform into a water arena thanks to a built‑in concrete pool, allowing fully staged water circus performances at a time when most people had never seen anything like it. Outside, exotic “people’s caravans” and ethnographic exhibitions in the park added to the sense that Városliget was a gateway to the wider world.

Beketow’s Horses and a Golden Age

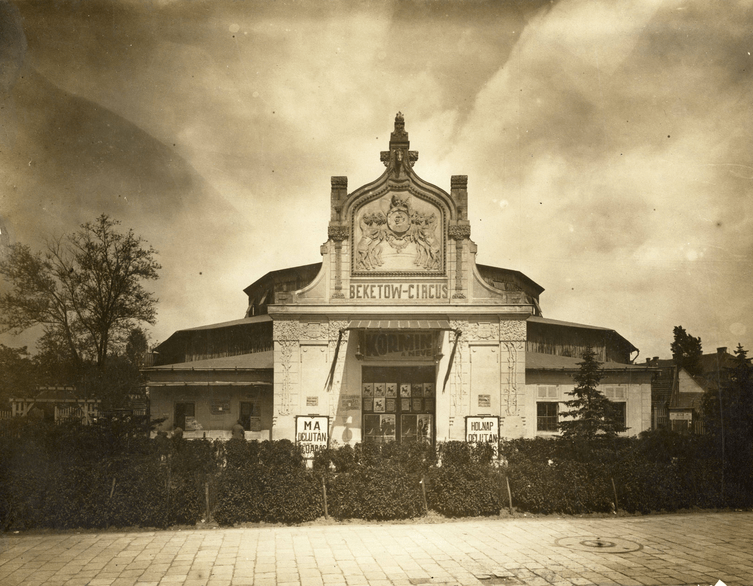

At the turn of the 20th century, the circus entered a glamorous new era under the leadership of Matvej Ivanovics Beketow, a former soldier turned clown and master horse trainer from the Russian Empire. He took over the lease in 1904 and invested heavily in the building, renovating it, upgrading its façade and eventually moving it to a more prominent spot near the boulevard—still inside the Zoo area, but set apart with its own entrance and emblematic street front.

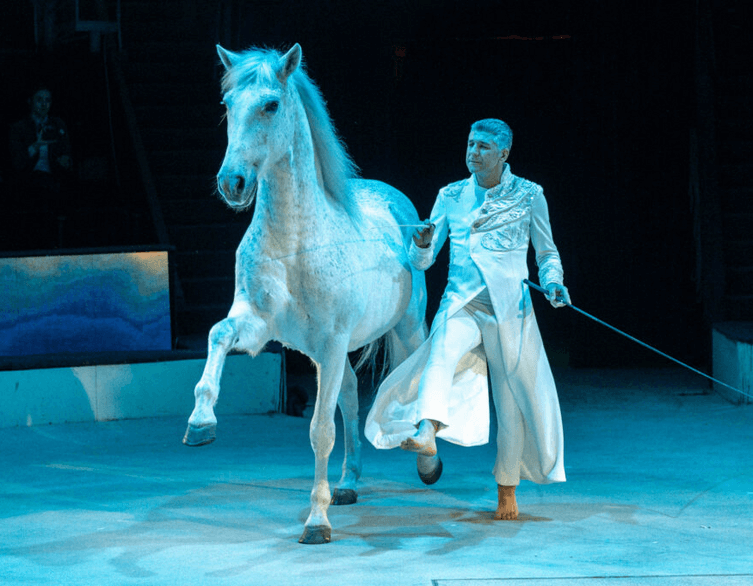

Beketow’s passion was the horse, and he was not shy about proving it. The circus sometimes kept around a hundred horses, and his equestrian acts became the undisputed highlight of the shows. Imagine stepping into the dim hall and suddenly the ring filling with a choreographed storm of galloping animals, riders standing upright on their backs, costumes glittering in the arc‑lights. For audiences used to carriages and workhorses, this elevated everyday reality into something dreamlike, turning the horse into a noble stage partner rather than a simple tool.

Image source: Capital Circus of Budapest

The façade of the building reflected this pride: its emblem showed three rearing circus horses on each side of a portrait of Beketow, framed by a horseshoe. It was much more than a logo—it was a statement that Budapest’s circus saw itself at European level. During this period, the circus also opened its ring to other forms of entertainment. In 1911, the visionary theatre director Max Reinhardt staged his monumental production of “Oedipus” here, transforming the circus into a temporary classical theatre and proving that the round ring could host both myth and acrobatics.

War, Ruin and a May Day Resurrection

The first half of the 20th century brought financial crises and eventually war. Beketow’s fortunes declined, and after years of struggling, he went bankrupt and took his own life in 1928. His son Sándor tried to keep the circus going, shifting towards more variety‑style programmes with partner Rezső Árvai, but attendance dropped and eventually they had to surrender the lease.

Best deals of Budapest

In the 1930s, the building hosted different tenants, from the famous Busch Circus with its eye‑catching water circus shows to the Vígszínház theatre company, which temporarily moved in and staged “The Star of the Circus” with beloved film actors of the era. In 1936, entrepreneur György Fényes took over as director and deliberately steered the circus towards glamorous revue‑like productions. He even added the word “varieté” into the name to signal a more cosmopolitan programme. The clown Gábor Eötvös, who would later become an iconic figure of Hungarian circus, often performed under Fényes, and his musical clowning was so refined that it drew praise from none other than Charlie Chaplin.

Then came 1944. As bombing raids intensified over Budapest, the circus closed its doors. The building suffered serious damage, and at one point German troops even used it as a temporary stable. Locals later dismantled parts of the ruined structure for firewood during the hard winter months. For many, it seemed that the era of the circus in Városliget might be over.

But on 1 May 1945—barely months after the siege of Budapest ended—the ring lit up again. Despite the broken walls and patched‑up benches, a May Day holiday programme was put together by Rezső Árvai and the Göndör brothers: Ferenc, a star of a famous teeterboard troupe, and Miklós, better known under his stage name, the magician Corodini. For a city scarred by war, walking into that damaged but functioning circus and seeing acrobats launching themselves into the air and rabbits pulled out of hats was more than entertainment; it was a promise that normal life and joy could return.

Nationalisation and the Rise of Hungarian Circus Art

In 1949, like many cultural institutions, the circus was nationalised and took on the name that visitors see today: Fővárosi Nagycirkusz, the Capital Circus of Budapest. Under state ownership, circus was officially recognised as a legitimate performing art, on par with theatre or opera. This changed the lives of performers: families who had travelled with their own small circuses for generations were reorganised into a nationwide network of state circuses, and in 1954 the Hungarian Circus and Variety Company was established to manage them.

One of the most significant developments was the founding of the State Artist Training Institute—today known as the Baross Imre Artist and Performing Arts Academy. For the first time, children from outside traditional circus families could apply and train from around the age of eleven or twelve, learning juggling, aerial work, acrobatics and clowning alongside dance and general education subjects. Many of the students who grew up in its halls went on to perform in world‑famous circuses and at top festivals, turning “Hungarian style” acts—like explosive teeterboard numbers and high‑speed jockey pieces—into recognisable signatures on the global circus scene.

For audiences, the post‑war decades felt like a golden era. The circus was packed with families who bought tickets months ahead, and Hungarian artists touring abroad sent back stories and photographs that fed into a sense of national pride. At home, the Capital Circus staged increasingly ambitious productions, even as its original building aged and demanded more and more maintenance.

Saying Goodbye to the Old Circus and Building a New One

By the late 1950s, engineers and directors knew the old Wulff–Beketow building could not last forever. It had undergone major renovations, but its structure was outdated, and plans for a new, modern circus were quietly drawn up. In the mid‑1960s, the decision was finally made: a completely new building would rise on the same spot, with a design that combined Soviet‑inspired stone circus architecture with local innovations.

Before the demolition, the circus staged a bittersweet farewell programme titled “The Circus Says Goodbye”. Many artists who had performed there for decades returned to step into the ring one last time. For them, it was like saying goodbye to an old friend: the worn wooden steps, the backstage labyrinth, the specific echo of the ring when the drum rolled before a somersault. When the final curtain fell, the building was taken down, and performances moved into a big top erected at Dózsa György út for the transition period.

The new circus building—often affectionately referred to as the “circus palace”—opened on 14 January 1971. Its design is striking: a round, concrete structure whose vast unsupported roof resembles a permanent tent. Inside, it was equipped with up‑to‑date sound and lighting, modern dressing rooms that could host up to 150 performers, comfortable stalls, and proper backstage facilities for animals, including modular, safe cages. The first director of this new era was Mária Eötvös, a descendant of a legendary circus dynasty and, to this day, the only woman to have led the institution. Her presence alone is a story: a female director at the helm of a major state circus in the early 1970s was a remarkable milestone in a traditionally male‑dominated field.

Legendary Moments and Behind‑the‑Scenes Stories

Over the decades, the Capital Circus of Budapest has accumulated countless stories that give the venue its unmistakable character.

There is, for instance, the story of the nearly sold‑out show during a sudden snowstorm, when public transport faltered and many assumed the performance would be cancelled. Instead, the artists, technical crew and the few dozen hardy audience members who made it to Városliget agreed to go ahead anyway. The result felt more like an intimate private performance than a regular show: artists playing directly to the small crowd, clowns improvising with the empty seats, and the ringmaster joking that the snow outside had only made the circus feel even more magical.

Or the tale of the musician who famously ran from the orchestra pit to the ring after an acrobat lost balance and descended too close to the band’s platform. The story goes that the violinist instinctively threw his instrument aside and helped catch the artist, turning what could have been an accident into an unscripted moment of solidarity that the audience applauded even more than the previous trick. In Budapest’s circus culture, musicians, dancers and acrobats are not separate worlds but a tight‑knit family sharing the same risks and triumphs.

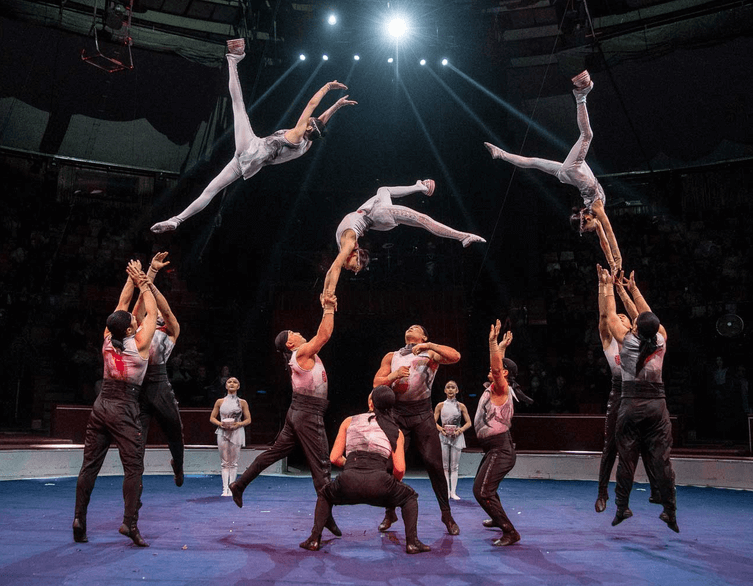

The Budapest International Circus Festival has its own trove of anecdotes. At one early edition, a young troupe arrived from abroad after a gruelling journey with lost luggage and delayed flights, with barely any time to rehearse in the ring. Their act combined juggling and acrobatics with theatrical storytelling, and everyone backstage worried that the lack of preparation would show. Instead, the adrenaline and pressure brought out their best performance, and they left the ring to a standing ovation, later receiving one of the festival’s top prizes. Stories like this travel quickly through the global circus community and add to Budapest’s reputation as a supportive but demanding stage where excellence is recognised.

More Than a Show: A Cultural and Educational Hub

Today, the Capital Circus of Budapest functions as a multi‑layered cultural institution. On the surface, it presents seasonal productions that change several times a year, often built around a strong narrative theme. These shows blend classic acts—trapeze, tightrope, clowns, animal presentations—with contemporary staging: cinematic lighting, original scores, and choreographies that draw from ballet, contemporary dance and even street styles.

Behind the curtain, there is an entire world dedicated to preserving and rethinking circus art. The Hungarian Circus Arts Museum, Library and Archive collect costumes, apparatus, posters, photographs, film reels, sheet music and personal documents from artists and families. Their mission is not only to store objects but to keep memories alive: to tell the stories of travelling dynasties, everyday rehearsals, and the small human details that never make it into official histories.

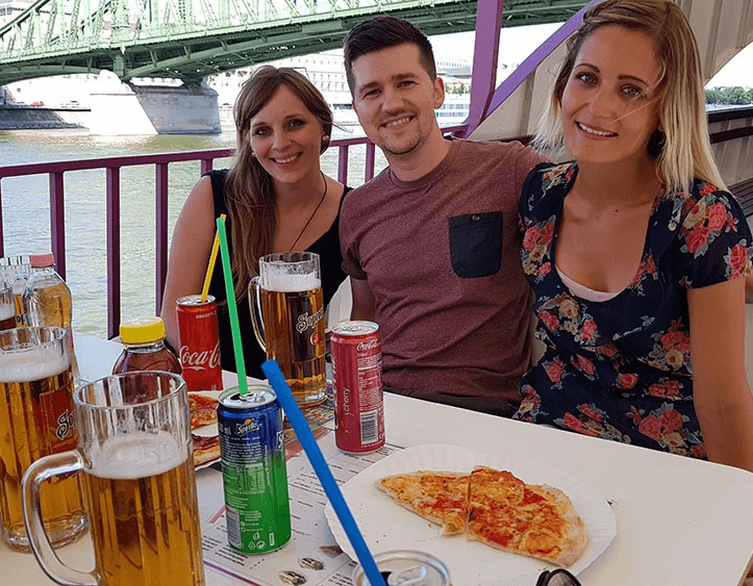

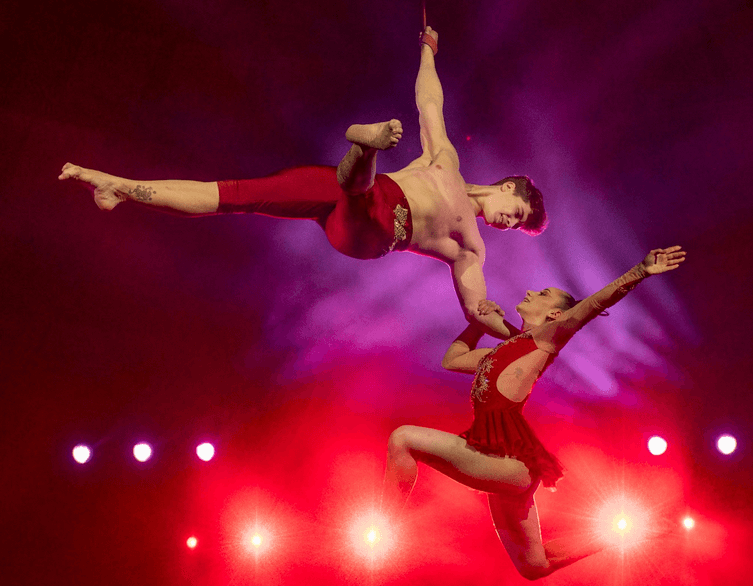

Moving together

Image source: Capital Circus of Budapest

The circus has also become an educational laboratory. After performances, school groups can stay in the ring for “extraordinary lessons” where teachers and specialists use acrobatics and tricks to explain physics, mathematics, biology or literature. A teeterboard launch becomes a way to talk about force and trajectory; a story‑based show like “Holle anyó” (Mother Hulda) turns into a live literature lesson, exploring symbolism and character motives while children still feel the sawdust under their feet. For many young people, it is their first experience of learning in an environment where science and art meet so directly.

Inclusivity is another key focus. The circus has developed advanced audio‑description systems to make performances accessible to blind and partially sighted visitors, and it works continuously on physical and social accessibility so that people with different abilities and backgrounds can experience the same sense of wonder in the ring.

The Budapest Circus Experience for Today’s Visitor

For you as a visitor in Budapest, all of this history and backstage reality condenses into a couple of unforgettable hours. You emerge from the M1 metro at Széchenyi Bath, walk past the Zoo and the trees of Városliget, and find yourself standing in front of a round concrete building topped with flags. Inside, the foyer feels more like a theatre than a tent: cloakrooms, a buffet, posters of current and past shows, and the distant sound of the orchestra warming up.

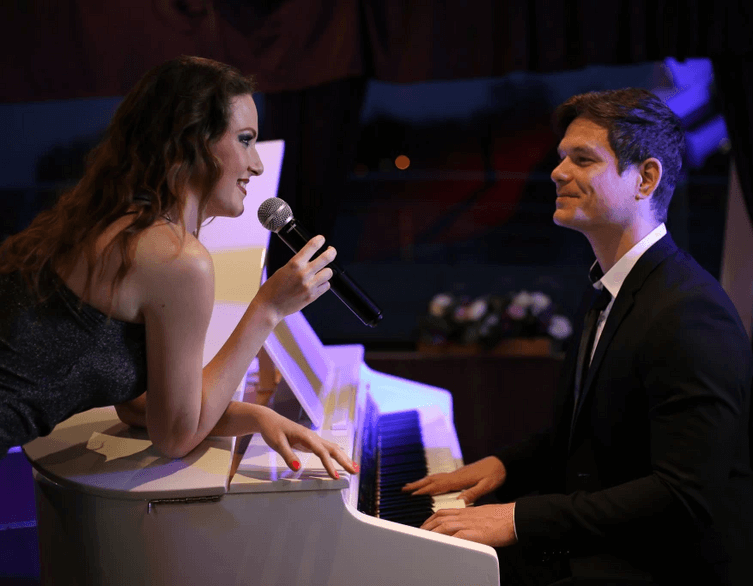

Image source: Capital Circus of Budapest

Once you take your seat and the lights dim, the atmosphere shifts into something both modern and timeless. You watch performers from all over the world—many trained or mentored in Budapest—step into the same ring where Beketow’s horses thundered, where wartime audiences found hope on a battered May Day, and where generations of Hungarian families have cheered, laughed and held their breath together.

The Capital Circus of Budapest is not just entertainment; it is a living story about how a city and an art form grow together. From Wulff’s fire‑safe iron walls to Beketow’s equestrian splendour, from post‑war resilience to the stone circus of 1971 and today’s ambitious festival culture, the ring in Városliget continues to reinvent itself while honouring its past.

Practical Information for Your Visit

Location and How to Get There

The Capital Circus of Budapest stands in Városliget at Állatkerti körút 12/A, right beside the Zoo and only a short walk from Heroes’ Square and Széchenyi Thermal Bath, making it easy to combine a performance with a full day in the City Park. The most atmospheric way to reach it is by the historic yellow M1 metro line towards Mexikói út; get off at Széchenyi Fürdő and follow Állatkerti körút for a few minutes until the round concrete circus building appears on your left.

Season, Schedule and Show Experience

Because it is a permanent stone building with a covered, climate‑controlled auditorium, the circus operates in all seasons, from hot summer days to snowy winter afternoons. Performances usually last about two hours including a short interval, and the mix of acrobatics, live music and visual storytelling tends to keep even younger children absorbed throughout. The seating is steeply tiered and relatively intimate, so you can enjoy a good view of the ring and aerial acts even from the middle rows.

Tickets and Booking Tips

Tickets are available online through official partners as well as at the on‑site box office, which generally opens from late morning into the evening on show days. It is wise to book in advance for weekends, public holidays and for performances during the Budapest International Circus Festival in January, as these dates often sell out quickly. Prices are usually moderate by Western European standards, and family packages or reduced‑price categories often make the experience accessible for larger groups.

Facilities and Family‑Friendly Details

Arriving a little early gives time to collect tickets, leave coats at the cloakroom and explore the foyer, where posters and displays introduce the current programme and the history of the circus. Inside the building you will find modern restrooms, a buffet selling snacks and drinks, and space to store prams and bulky winter clothes so you can watch the show comfortably. Most performances are in Hungarian, but foreign visitors rarely find this a barrier because the humour, music and acrobatics carry the story visually, making the experience enjoyable regardless of language.

Combining the Circus with a Day in Városliget

Thanks to its location in the heart of the City Park, the circus fits naturally into a wider sightseeing itinerary that might include the Zoo, Széchenyi Thermal Bath, Vajdahunyad Castle or the Museum of Fine Arts. Many visitors spend the day exploring Városliget, then end with an afternoon or evening performance, stepping back out afterwards into the illuminated park with the circus dome glowing behind them as a memorable finale to their Budapest day.

Related news

Related attractions