Hidden Treasure at Liberty Bridge: Budapest’s Smallest Transportation Museum

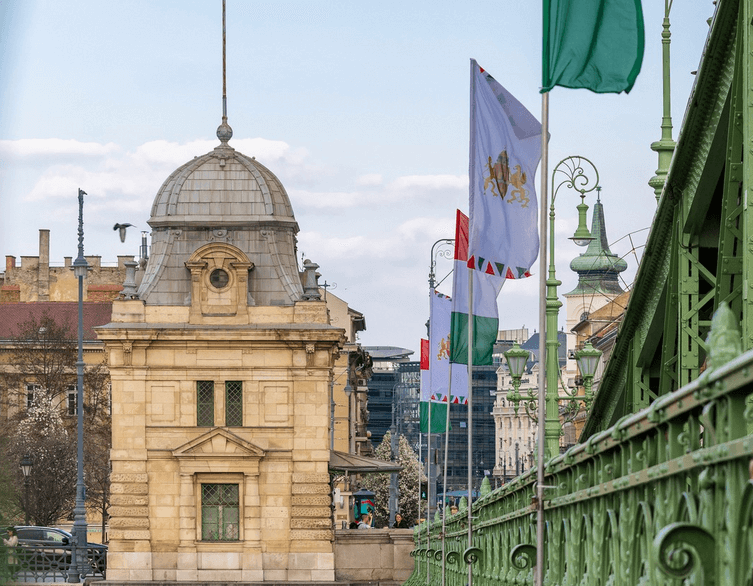

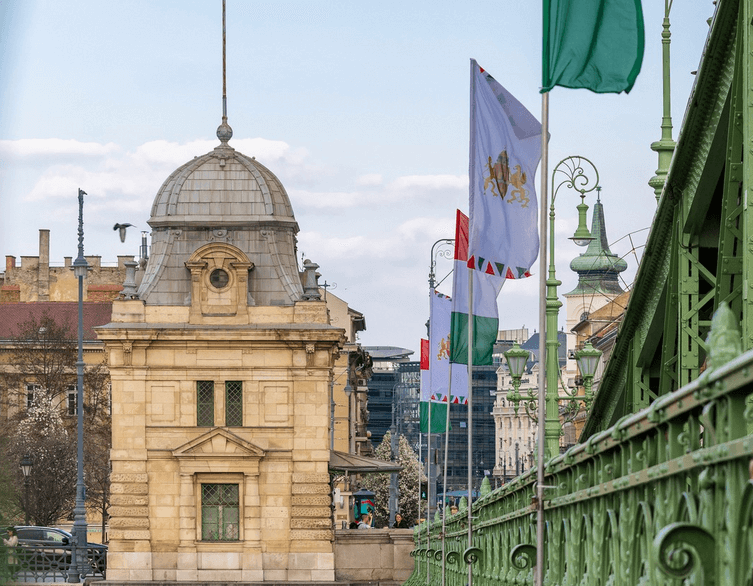

Tucked away at the foot of one of Budapest’s most beautiful bridges lies a charming secret that most tourists walk right past—a tiny customs house hiding a fascinating glimpse into the city’s history. The Vámszedőház (Customs House) at Liberty Bridge isn’t just a picturesque building you spot from your tram window; it’s home to what might be the world’s smallest transportation museum, offering an intimate journey through Budapest’s bridge-building legacy.

The Story Behind the Little Houses

If you’ve ever crossed Liberty Bridge on the Pest side, you’ve probably noticed two small, elegant buildings standing guard at the bridgehead. These charming structures aren’t just architectural decoration—they’re survivors of a bygone era when crossing the Danube came with a price tag. From 1703 until November 30, 1918, anyone wanting to cross between Buda and Pest had to pay a toll, and these customs houses were where the money changed hands.

The two cities received the right to collect tolls in 1703, initially charging everyone who crossed the river by any means. Before the Chain Bridge opened, people paid these tolls on pontoon bridges that connected the two banks. Interestingly, nobles and city citizens were exempt from payment until 1849. The cities didn’t operate the bridges themselves but leased them to private operators who paid a fixed annual fee and kept whatever additional revenue they collected.

Everything changed in 1849 when the toll collection rights transferred to the private company that built the Chain Bridge, with one crucial difference—now everyone had to pay, regardless of status. This marked one of Hungary’s first steps toward equal taxation. From 1870 onward, after the state purchased these rights from the Chain Bridge Company, the government collected tolls not just for bridge crossings but even for river ferry passages, charged on top of the regular fare.

A System That Funded a City’s Growth

Originally, every bridge in Budapest had its own pair of customs houses, built not merely as ticket booths but as multi-functional facilities. Take the Chain Bridge customs houses, for example—though they appear single-story in old photographs, comparing the human figures reveals their true scale. These buildings actually contained four internal levels: basement, ground floor, first floor, and upper floor. Inside, you’d find not only ticket windows but also tobacco shops, various service rooms, and offices responsible for bridge operations. After electricity arrived, each space—whether offices, rented shops, or service areas—had its own meter to simplify accounting.

The toll revenue served a vital purpose, financing Budapest’s explosive 19th-century development. The money helped repay the 1870 loan that built the Grand Boulevard and the Danube embankments, transforming Budapest from two separate towns into a unified metropolis. Even when the government reduced tolls by half in 1885 and eliminated collection on the Buda side (making payment necessary only when traveling from Pest to Buda), the system continued funding new infrastructure.

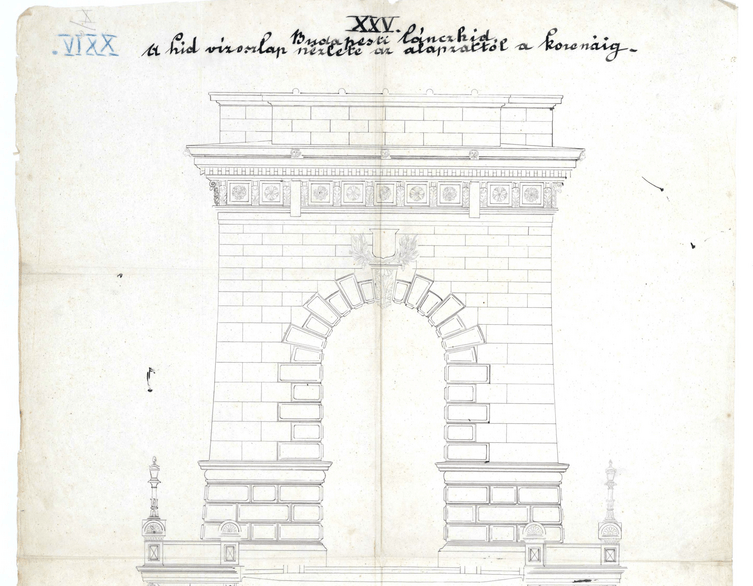

Margaret Bridge presents an amusing footnote to this history. When the bridge opened in 1876, the customs houses weren’t finished—toll collectors worked from wooden shacks for nearly eight years until the permanent buildings were completed in 1884. Meanwhile, Liberty Bridge (originally Franz Joseph Bridge) sparked debates during its 1894 design competition, with judges specifically evaluating the aesthetic merit of the proposed customs houses as part of the winning criteria.

The Last Days of the Toll System

By the early 20th century, public sentiment had turned decisively against bridge tolls. Newspapers, citizen groups, and the Budapest city government repeatedly petitioned for their abolition. The tolls generated only about 2 million crowns annually—barely enough to cover bridge maintenance, let alone justify the inconvenience they caused thousands of daily commuters. The Social Democratic newspaper Népszava called the toll system “an annoying and harmful remnant of medieval institutions” that “unfairly taxes people: the count pays 4 fillérs, and so does the day laborer.”

Finally, on November 30, 1918, Mihály Károlyi’s government abolished bridge tolls as one of its first revolutionary reforms. The Újság newspaper celebrated: “On Saturday, November 30, at exactly midnight, you won’t need to stop at bridge customs houses, unbutton yourself in the night cold, laboriously find two iron 2-fillér coins, and pay the bridge or tunnel toll.” Photographer János Müllner captured the historic final moments when the last travelers paid to cross the Chain Bridge.

After 1918, the customs houses found new purposes—converted into service apartments, small shops, tobacco stands, and administrative offices. At Margaret Bridge, the island-side customs houses continued collecting money, though now for Margaret Island entry fees rather than bridge tolls (visitors paid to enter the island until 1948).

Survival Against the Odds

Originally, every bridge in Budapest had its own pair of customs houses, but World War II changed everything. When German forces retreated in 1944-45 and destroyed the city’s bridges, most of these buildings were lost forever. During post-war reconstruction, the remaining customs houses were demolished—with two notable exceptions.

Only Liberty Bridge’s two Pest-side customs houses survived, though for practical rather than sentimental reasons. The Chain Bridge customs houses, for instance, stood where the modern roundabout now exists, making them impossible to preserve. At Elizabeth Bridge, even if engineers had reconstructed the original suspension design, they would have eliminated the massive 17-meter monument bases (originally built to reinforce bridge foundations after construction mishaps caused the Buda side to slip 33 millimeters).

Today, the southern Liberty Bridge customs house serves as the bridge master’s office, while the northern building houses the museum. The Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport first received this building in 1997, opening a small bridge history exhibition that operated irregularly—visitors could only enter when the bridge master or a museum colleague unlocked the doors. Technical issues eventually forced its closure, and the building sat largely unused for years.

A Museum Reborn

In May 2024, after extensive interior renovation, the museum finally reopened with a permanent exhibition spanning just 26 square meters (2×13 square meters across two floors)—quite possibly the world’s smallest transportation museum. Despite its compact dimensions, the exhibition delivers remarkable depth, carefully selecting stories and artifacts that illuminate Budapest’s transformation without overwhelming visitors with excessive detail.

Inside the Exhibition: Ground Floor

Step through the entrance and you’ll immediately immerse yourself in the world of Liberty Bridge and Budapest’s toll collection system. The ground floor dedicates itself entirely to explaining how this particular bridge and its customs house functioned as part of the city’s economic infrastructure.

Original toll tokens take pride of place among the artifacts—these small metal discs served as receipts proving payment, allowing passage across the bridge. The exhibition displays several varieties, showing how designs evolved over decades. Alongside these, you’ll find archival photographs demonstrating the payment process: families queuing at ticket windows, uniformed collectors checking tokens, horse-drawn carriages and early automobiles waiting their turn.

The displays explain in clear, accessible language (both Hungarian and English) how toll revenues financed Budapest’s grandest 19th-century projects. You’ll learn that the money didn’t simply maintain bridges—it funded the Grand Boulevard, riverside promenades, and countless infrastructure improvements that transformed two provincial towns into a modern European capital. Informational panels break down the toll rates for different users: pedestrians paid the least, while freight wagons and carriages paid significantly more, with public transport services negotiating flat annual fees.

One fascinating section explores the daily operations of the customs house itself. Beyond toll collection, this building served multiple functions—bridge maintenance crews stored equipment here, supervisors maintained offices, and tobacco shops catered to crossing travelers. The exhibition reveals how each functional space was carefully tracked and metered once electricity arrived, creating a surprisingly modern approach to facilities management.

Inside the Exhibition: Upper Floor

Climbing the narrow staircase to the upper level transports you into the broader narrative of Budapest’s bridge history. Here, the focus expands from Liberty Bridge specifically to encompass all the bridges that shaped the city’s development, exploring the intimate relationship between these engineering achievements and urban growth.

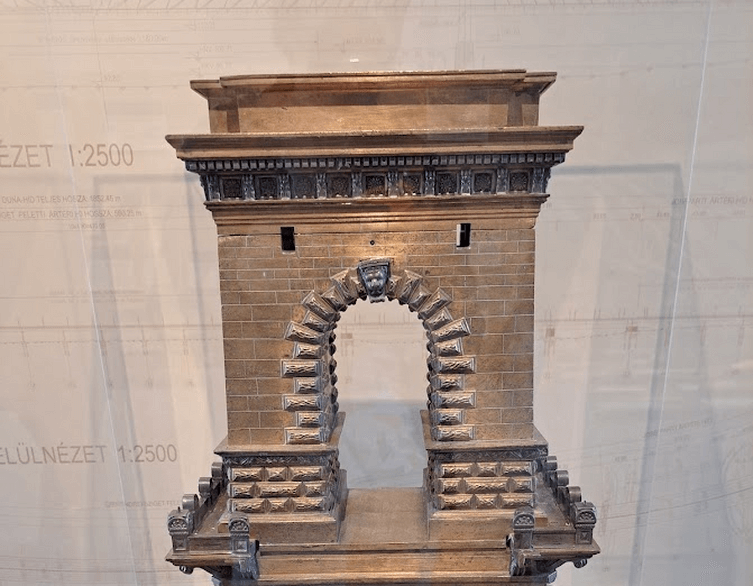

The centerpiece of this floor is the collection of artifacts from various Budapest bridges, each telling its own story. The Lánchíd (Chain Bridge) features prominently with a detailed 1913 model of its monumental gateway, crafted during major renovations. This miniature masterpiece allows you to appreciate architectural details impossible to see from street level. Nearby sits an authentic replica of the ceremonial trowel used during the bridge’s 1842 cornerstone laying ceremony—a tangible link to the moment when Budapest’s first permanent Danube crossing began taking shape.

Image by Cacor

An 1833 surveying map of the Danube reveals the river before bridges tamed its crossings. The detailed cartography shows ice flow patterns, flooding zones, and the natural obstacles that engineers would need to overcome. Comparing this historical document to modern maps demonstrates how dramatically bridges transformed not just transportation but the river itself.

Margaret Bridge contributes perhaps the exhibition’s most poignant artifact: a decorative crown element recovered from the Danube in 2003. This piece spent nearly six decades underwater after the bridge’s 1944-45 destruction, emerging only when unusually low water levels exposed the middle pillar’s foundation. The salvaged metalwork bears visible signs of its long submersion—corrosion, discoloration, water damage—making it a powerful memorial to wartime devastation and post-war renewal.

Elizabeth Bridge appears through a striking angel head that once adorned the crest atop the original suspension bridge. This delicate sculpture, somehow preserved when the rest of the bridge was destroyed, offers a glimpse of the elaborate decorative program that characterized Budapest’s pre-war bridges. Informational panels explain how the new Elizabeth Bridge, completed in the 1960s, adopted a dramatically different modernist aesthetic, making artifacts like this angel head the only surviving evidence of the original’s ornate beauty.

Best deals of Budapest

Liberty Bridge itself receives special attention through a unique railing element from the immediate post-war reconstruction period. This piece represents a design used only briefly—simplified for quick rebuilding—before later renovations restored the original decorative railings. You literally cannot see this design anywhere else in Budapest, making it a museum-exclusive glimpse of a transitional moment in the bridge’s history.

Throughout both floors, wooden paving blocks from various bridges sit in display cases, their worn surfaces testament to decades of traffic. Original rivets, construction fasteners, and structural elements provide tactile evidence of 19th and 20th-century engineering techniques. A wooden foundation pile from the Chain Bridge—driven deep into the riverbed to support massive stone piers—demonstrates the monumental scale of these projects and the ingenuity required to build in a powerful river environment.

Modern Technology Meets Historic Artifacts

The exhibition skillfully integrates contemporary technology to enhance the visitor experience without overwhelming the intimate space. Virtual reality headsets offer the most dramatic enhancement—donning them transports you to 1940s Budapest, allowing you to see the cityscape as it appeared before wartime devastation. You’ll stand on the reconstructed Chain Bridge, gaze at the original Elizabeth Bridge suspension design, and witness Margaret Bridge in its pre-destruction glory. This immersive experience creates emotional connections impossible through static displays alone.

Animated displays bring bridge construction sequences to life, showing how massive stone piers were sunk into the riverbed, how iron frameworks were assembled piece by piece, and how engineers solved problems that would have seemed insurmountable to earlier generations. These animations make complex engineering concepts accessible even to visitors without technical backgrounds.

Informational panels throughout both floors maintain a perfect balance between comprehensive information and readability. They explore construction techniques ranging from the Chain Bridge’s groundbreaking suspension design to Megyeri Bridge’s modern cable-stayed structure, explaining how each approach solved specific challenges. The panels also illuminate the social history behind the engineering—how bridges influenced neighborhood development, where people chose to live and work, and how transportation networks evolved in response to new crossing points.

Liberty Bridge: A Symbol of National Pride

The customs house makes a particularly appropriate home for this exhibition because Liberty Bridge itself represents a watershed moment in Hungarian engineering and national identity. Constructed between 1894 and 1896 as part of Hungary’s millennial celebrations marking 1,000 years since Magyar settlement, this was the first major Budapest structure designed by a Hungarian engineer—János Feketeházy—and built entirely from Hungarian materials, a powerful statement during the Austro-Hungarian era.

Emperor Franz Joseph inaugurated the bridge on October 4, 1896, in a grand ceremony where he hammered in the final rivet, allegedly crafted from silver. Originally christened Franz Joseph Bridge in his honor, it was renamed Liberty Bridge following World War II reconstruction in 1946. At just 333 meters long, it remains Budapest’s shortest bridge, but compensates for its modest length with extraordinary character and beauty.

The bridge’s distinctive Art Nouveau design, painted in signature green, features ornate lamp posts, intricate metalwork, and four tall pillars crowned with statues of the turul—a mythical falcon-like bird from Hungarian mythology symbolizing power and freedom. World War II brought devastating damage when German forces destroyed the bridge’s central section, yet remarkably, engineers successfully reconstructed it almost identically to the original. Subsequent renovations in 1986 and 2007-2008 restored all historical decorative elements, including the Hungarian coat of arms and Holy Crown, even reinstalling the elaborate central railing that had been simplified during earlier repairs.

Visitor Information

Location and Access

The customs house museum sits at 1056 Budapest, Fővám tér, directly at Liberty Bridge’s Pest end. This prime location places you adjacent to the magnificent Great Market Hall (Nagyvásárcsarnok), one of Budapest’s most popular tourist destinations, making it incredibly easy to combine both attractions in a single visit.

Public transportation couldn’t be more convenient. Tram lines 2, 47, and 49 all stop at Fővám tér, providing direct access from anywhere along the riverside and beyond. The M4 metro line’s Fővám tér station sits just steps away, connecting you to the broader Budapest metro network. If you’re exploring the Pest riverfront on foot, you’ll naturally pass right by the customs house.

Opening Hours

The museum welcomes visitors daily from 11:00 AM to 6:00 PM (18:00), seven days a week including weekends and most holidays. This consistent schedule makes visit planning simple—you don’t need to worry about complicated weekday versus weekend hours or unexpected closures. However, it’s worth noting that the museum occasionally extends hours for special events like the annual Night of Museums in June, when it typically stays open until midnight.

Admission and Tickets

Best of all, admission is completely free. No tickets, no advance reservations, no hidden costs—just walk in during opening hours and explore at your leisure. This accessibility makes the museum welcoming to everyone, from budget-conscious backpackers to families with multiple children to curious locals who might visit repeatedly.

Time Required

The intimate 26-square-meter space means most visitors spend 15 to 30 minutes exploring both floors, though enthusiasts of engineering history, transportation, or Budapest’s past might linger 45 minutes or an hour, especially if they engage with the VR experience and read all the informational panels thoroughly. The compact format works to your advantage—you get a concentrated dose of fascinating information without the exhaustion that often accompanies large museum visits.

Accessibility

The ground floor is easily accessible for all visitors. However, reaching the upper floor exhibition requires climbing a narrow staircase typical of 19th-century buildings. Visitors with mobility limitations should be aware of this constraint, though the ground floor alone offers substantial content worth experiencing.

Language

All exhibition text appears in both Hungarian and English, making the museum fully accessible to international visitors. The bilingual approach extends to informational panels, artifact labels, and interactive displays, ensuring you won’t miss any insights regardless of your language background.

Photography

Photography is generally permitted throughout the exhibition, allowing you to capture favorite artifacts and moments. The compact space and good lighting make for excellent photo opportunities, though you’ll want to be respectful of other visitors in the small quarters.

Museum Shop

Before leaving, explore the small gift shop featuring transportation-themed merchandise. You’ll find train-themed playing cards, 2025 calendars showcasing vintage buses and trams, unique plush toys and scale models, specialized books about Budapest’s engineering heritage, and various smaller souvenirs. These items make wonderful mementos for transportation enthusiasts or anyone seeking meaningful gifts beyond typical tourist trinkets. Proceeds support the museum’s ongoing operations and exhibitions.

Combining Your Visit

The customs house’s location makes it perfect for combining with other nearby attractions. The Great Market Hall, just steps away, offers Budapest’s best produce, crafts, and food stalls—arrive when the museum opens at 11:00, explore the market first (it opens at 6:00 AM on weekdays), then visit the customs house before or after lunch. The riverside promenade stretching along the Danube invites leisurely walks with stunning views. During warmer months, consider visiting the museum, then walking across Liberty Bridge to explore Gellért Hill or the famous Gellért Baths on the Buda side.

Special Considerations

The museum’s small size means it can feel crowded if multiple groups arrive simultaneously. Visiting during weekday mornings or early afternoons typically ensures quieter experiences with more space to linger over favorite displays. Summer weekends tend to be busiest, particularly when Liberty Bridge closes to vehicle traffic and becomes a popular gathering spot.

Experience the Bridge with New Eyes

After exploring the exhibition, step outside and walk onto Liberty Bridge itself for an entirely transformed perspective. Armed with newfound knowledge about toll collection, bridge construction, and urban development, you’ll notice details previously overlooked—the careful restoration work preserving original elements, the engineering ingenuity solving complex challenges, the symbolic decorations celebrating Hungarian identity.

During summer weekends, the bridge sometimes closes to vehicle traffic, transforming into an impromptu social gathering space. Locals and tourists sit on the lower structural beams, dangling their legs above the Danube while enjoying drinks and conversations against spectacular views. This contemporary usage would surely amaze those 19th-century commuters who grudgingly paid their 4 fillérs to cross—the bridge has evolved from utilitarian necessity to beloved public space embodying Budapest’s character.

Why This Hidden Gem Matters

In a city overflowing with grand palaces, dramatic monuments, and sweeping panoramas, this tiny museum offers something refreshingly different—an intimate, focused examination of infrastructure that made modern Budapest possible. It reminds us that history encompasses not just monarchs and battles but also everyday systems connecting communities and building cities.

The exhibition succeeds precisely because it avoids encyclopedic comprehensiveness. Instead, curators carefully selected stories and artifacts illuminating key moments in Budapest’s development, making complex engineering history accessible and engaging for general audiences. Whether you’re a transportation enthusiast, history buff, architecture lover, or simply curious about the city you’re exploring, this little customs house provides insights unavailable elsewhere.

Few tourists discover this hidden treasure, meaning you’ll likely enjoy the space in peaceful solitude—a rare luxury in busy Budapest. It represents the kind of authentic, off-the-beaten-path experience that makes travel truly memorable, where unexpected discoveries yield deeper understanding of place and culture. When you subsequently cross Liberty Bridge and admire its elegant green spans stretching across the Danube, you’ll perceive not merely a bridge but a testament to ambition, resilience, and the enduring connections defining Budapest’s identity.

Related news

Related events

Related attractions