Saint Stephen I of Hungary: The King Who Founded a Nation

Discover the remarkable story of Hungary’s first king, whose vision transformed a collection of nomadic tribes into one of Europe’s most enduring Christian kingdoms.

When visitors walk through the streets of Budapest today, they encounter the legacy of one man at every turn. From the magnificent St. Stephen’s Basilica dominating the Pest skyline to the Holy Right Hand venerated within its walls, the presence of Saint Stephen I of Hungary (István I, 975-1038) remains deeply woven into the fabric of Hungarian identity more than a thousand years after his death.

From Vajk to Stephen: The Making of a Christian King

Born around 975 CE as Vajk (a name of Turkic origin meaning “hero” or “leader”), the future king entered a world in transition. His father, Grand Prince Géza, had already begun steering the Hungarian tribes toward Christianity and Western orientation, recognizing that survival in medieval Europe required strategic alliances with Christian powers.

The young prince’s transformation began with his baptism between 985-989, when he received the name Stephen (István in Hungarian) after the first Christian martyr. This wasn’t merely a name change—it symbolized a fundamental shift in Hungarian destiny from East to West.

A Strategic Marriage That Changed History

In 995, Stephen married Gisela of Bavaria, daughter of Duke Henry II of Bavaria. This union wasn’t just romantic—it was a masterstroke of medieval diplomacy that brought Hungarian politics into the heart of European royal networks. Gisela arrived with a retinue of German knights, clergy, and craftsmen who would prove crucial in Stephen’s later campaigns.

The Crown That Created a Kingdom

The most pivotal moment in Hungarian history occurred on January 1, 1001 (December 25, 1000, according to the Julian calendar then in use), when Stephen was crowned King of Hungary. But this crown came with a remarkable story.

Stephen had sent Astrik, the Abbot of Pannonhalma, to Rome to negotiate with Pope Sylvester II and Emperor Otto III. The young king sought not just recognition, but something far more valuable: apostolic authority. This papal privilege allowed Stephen to establish bishoprics and appoint church officials independently, ensuring Hungary’s ecclesiastical independence from the German Empire.

The coronation itself was revolutionary. Unlike his predecessors who ruled by tribal consensus, Stephen claimed authority “by the Grace of God”—establishing the divine right of Hungarian kings that would endure for nearly a millennium.

Forging Unity Through Fire and Faith

Stephen’s path to unifying Hungary was far from peaceful. His greatest challenge came from Koppány, a powerful chieftain who claimed the throne based on ancient Hungarian customs, including the right to marry Stephen’s widowed mother, Sarolt.

The Battle That Decided Hungary’s Future

The decisive confrontation occurred around 998 near Veszprém. Stephen’s forces, including his German heavy cavalry and Hungarian warriors, faced Koppány’s traditional light cavalry army. The battle represented more than a power struggle—it was a clash between Hungary’s pagan past and Christian future.

Stephen’s victory was complete, but his treatment of Koppány shocked even medieval sensibilities. The defeated chieftain’s body was quartered, with parts displayed at four major fortresses (Győr, Esztergom, Veszprém, and Gyulafehérvár) as a grim warning to other potential rebels.

Completing the Conquest

Over the following decades, Stephen systematically brought the remaining Hungarian territories under central control:

- 1003: Defeated his uncle Gyula in Transylvania, incorporating Eastern Hungary

- 1015: Conquered the Bulgarian-allied chieftain Keán

- 1028: Final victory over Ajtony along the Maros River, completing Hungarian unification

Architect of Christian Hungary

Stephen’s greatest achievement wasn’t military conquest but institutional creation. He transformed Hungary from a loose confederation of tribes into a centralized Christian state that would endure for centuries.

Revolutionary Church Organization

Stephen established Hungary’s ecclesiastical structure with unprecedented scope:

- Two archbishoprics: Esztergom and Kalocsa

- Eight bishoprics spanning the kingdom

- Numerous monasteries and churches

His famous law requiring every ten villages to build and maintain a church wasn’t just about religion—it was about creating local administrative centers that strengthened royal authority.

The County System

Stephen replaced tribal territories with counties (vármegyék) administered by royal officials called ispáns. This system, centered on fortified strongholds, became the backbone of Hungarian administration and survived until the 20th century.

Legal Innovation

Stephen’s law codes, which begin Hungary’s thousand-year legal tradition, addressed everything from religious observance to property rights. Notable provisions included:

Best deals of Budapest

- Mandatory church attendance on Sundays

- Protection of widows and orphans

- Regulation of trade and commerce

- Severe penalties for pagan practices

Hungary as the Crossroads of Europe

Under Stephen’s rule, Hungary became a crucial link between Western and Eastern Europe. The king personally welcomed pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land, ensuring safe passage through Hungarian territory. This policy transformed Hungary into a preferred route to Jerusalem, bringing cultural exchange and economic prosperity.

Stephen established Hungarian hospices in Constantinople, Jerusalem, Ravenna, and Rome—creating the world’s first international network of diplomatic and religious facilities.

The Tragedy of Succession

Stephen’s greatest personal tragedy came in 1031 when his heir, Prince Emeric (Imre), died in a hunting accident, gored by a wild boar. This catastrophe not only devastated the aging king personally but created a succession crisis that would plague Hungary for decades.

Unable to find a suitable heir among his relatives, Stephen chose his nephew Peter Orseolo. This decision led to the blinding of his cousin Vazul, whose sons would later return to claim the throne, triggering decades of civil war after Stephen’s death.

Death of a King, Birth of a Legend

On August 15, 1038 (the Feast of the Assumption), Stephen died after 42 years of rule. According to legend, his final act was to offer his crown and kingdom to the Virgin Mary, making her Hungary’s eternal queen—a tradition maintained to this day.

He was buried in the magnificent Basilica of the Assumption he had built in Székesfehérvár, which served as Hungary’s coronation church for centuries.

The Saint King

In 1083, King Ladislaus I initiated Stephen’s canonization. On August 20, 1083, Stephen was declared a saint alongside his son Emeric and Bishop Gerard of Csanád. The ceremony was marked by miraculous healings and supernatural signs that convinced observers of Stephen’s holiness.

The Holy Right Hand

Stephen’s naturally mummified right hand, known as the Szent Jobb (Holy Right), became Hungary’s most sacred relic. According to tradition, when Stephen’s tomb was opened for canonization, his body had decomposed except for this hand—seen as divine confirmation of his sanctity.

Today, the Holy Right is displayed in St. Stephen’s Basilica in Budapest, and each August 20th, it’s carried in solemn procession through the capital’s streets.

Stephen’s Eternal Legacy

Modern Hungary’s Foundation

Every aspect of Hungarian statehood traces back to Stephen’s innovations:

- Constitutional monarchy (lasting until 1918)

- County administrative system (until 1950)

- Ecclesiastical organization (still functioning)

- Legal traditions (influencing modern Hungarian law)

Cultural Impact

Stephen’s influence extends far beyond politics:

- August 20th remains Hungary’s most important national holiday

- His image appears on Hungarian currency

- Countless churches, streets, and institutions bear his name

- The St. Stephen’s Basilica in Budapest houses his relic and serves as a pilgrimage destination

European Recognition

In 2000, Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople canonized Stephen for the Orthodox Church, making him the first saint recognized by both Eastern and Western Christianity since the Great Schism of 1054.

Visiting Stephen’s Budapest

Today’s visitors to Budapest can experience Stephen’s legacy firsthand:

St. Stephen’s Basilica: Admire the magnificent neo-classical dome and venerate the Holy Right Hand

Hungarian National Museum: View medieval artifacts from Stephen’s era

Buda Castle: Explore the site where Hungarian kings ruled for centuries

Matthias Church: Visit the gothic church where Hungarian kings were crowned

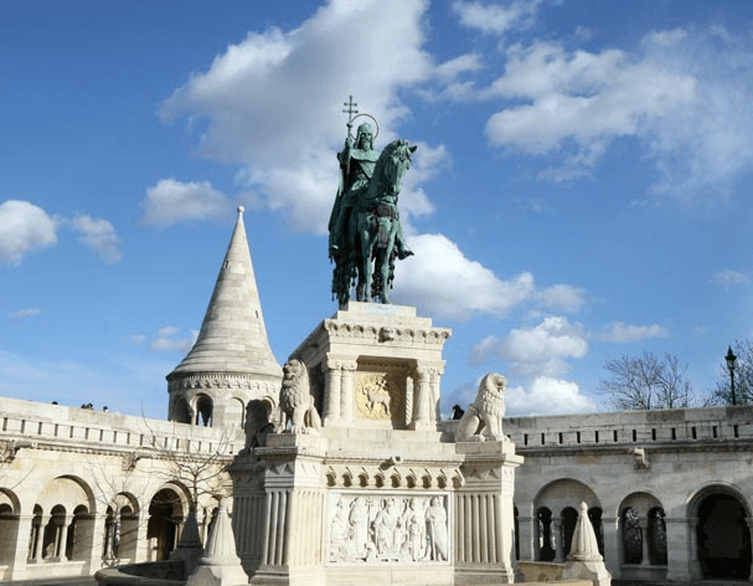

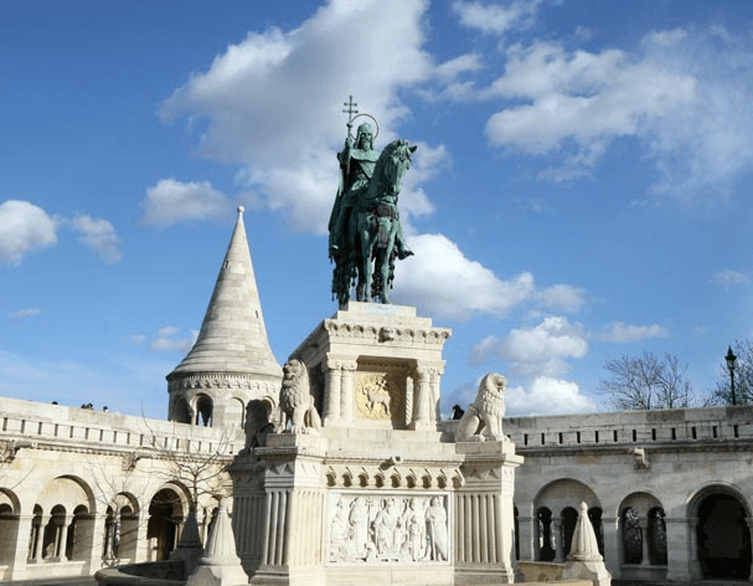

Visit his statues throughout the entire city: there are several statues erected in his memory all over Budapest, for example at the Fisherman’s Bastion, on Gellért Hill, and at Heroes’s Square.

The Eternal King

Saint Stephen I of Hungary achieved what few rulers in history have accomplished: he created a nation that has survived for over a millennium. His vision of Hungary as a Western, Christian kingdom while maintaining its unique Magyar character established a template that guided Hungarian development through centuries of triumph and tragedy.

For modern visitors to Budapest, Stephen represents more than historical curiosity—he embodies the Hungarian spirit of adaptation and survival. In transforming nomadic tribes into a European kingdom, Stephen created not just a state, but an identity that continues to define Hungary today.

His legacy reminds us that great leaders don’t merely govern—they transform civilizations. In the churches of Budapest, the layout of Hungarian counties, and the beating heart of Hungarian Christianity, Saint Stephen I remains very much alive, the eternal architect of the Hungarian nation.

Plan your visit to Budapest and discover the living legacy of Saint Stephen I. From the magnificent St. Stephen’s Basilica to the historic sites throughout the city, the first Hungarian king’s influence continues to shape one of Europe’s most fascinating capitals.

Related news

Related attractions