When Saints Hide in Goose Pens: The Delicious History of St. Martin’s Day in Budapest

Every November 11th, something magical happens across Budapest. Restaurants fill with the aroma of roasted goose, families gather for feasts that would make their medieval ancestors jealous, and children parade through streets carrying homemade lanterns like tiny stars brought down to earth. This is St. Martin’s Day, and if you’ve never heard of it, you’re missing out on one of Europe’s most charming and delicious traditions.

St. Martin’s Day sits in that sweet spot between Halloween and Christmas, borrowing a bit of mystery from one and anticipation from the other. It’s part harvest celebration, part religious feast, and entirely an excuse to eat goose and drink new wine until you waddle home happy. For visitors to Budapest, it offers a window into traditions that stretch back over a thousand years, rooted in both pagan agricultural customs and Christian legend.

The Man Who Couldn’t Hide from Destiny

The story begins with Martin of Tours, born around 316 or 317 CE in Savaria—modern-day Szombathely, Hungary. Yes, this saint is practically a local, which partly explains why Hungarians celebrate his day with such enthusiasm. Martin’s father was a Roman military tribune, and young Martin found himself conscripted into the army at age 15, though he’d already decided by age 12 that Christianity called to him more than military service ever could.

The most famous story about Martin happened on a freezing winter evening when he was still a soldier. Riding through the gates of Amiens in northern Gaul (now France), Martin encountered a beggar who’d been robbed and beaten, shivering in the bitter cold with barely any clothing. Without hesitation, Martin drew his sword—but instead of threatening the man, he cut his own military cloak in half and gave one piece to the beggar to wrap around himself. That night, Christ appeared to Martin in a dream, wearing that very piece of cloak, surrounded by angels. The vision transformed Martin’s life, and he was baptized at age 22.

But here’s where the goose comes in, and trust me, you need to know this part if you’re going to understand why Budapest goes goose-crazy every November. After leaving military service, Martin eventually became a hermit and founded what would become one of Europe’s oldest monasteries at Ligugé. His reputation for holiness spread, and in 371 CE, the people of Tours decided they wanted Martin as their bishop. There was just one problem: Martin really, really didn’t want the job. He considered himself unworthy and preferred his simple monastic life to the responsibilities and pomp of a bishopric.

So Martin did what any sensible person avoiding a promotion they don’t want would do—he hid. Specifically, he hid in a goose pen. The plan might have worked if geese weren’t such terrible co-conspirators. Their loud, insistent honking gave away his hiding spot, and Martin was dragged out of the goose pen and ordained as Bishop of Tours whether he liked it or not. The geese, having ruined Martin’s escape plan, have been getting roasted on his feast day ever since. It’s probably the most consequential act of barnyard betrayal in Christian history.

Best deals of Budapest

Where Paganism Meets Christianity Over a Roasted Bird

St. Martin’s Day didn’t emerge from nowhere—it landed perfectly on a date that already mattered to agricultural communities across Europe. Mid-November marked the end of harvest work, the point when farms finished preparing for winter. Barns were full, larders stocked, and farmers could finally exhale after months of backbreaking labor. This was party time, medieval style: feasts, dancing, markets, and tasting the new wine from that year’s grape harvest.

The Christian calendar adopted and adapted these celebrations. St. Martin’s Day became the last major feast before Advent began, when believers entered a 40-day fast preparing for Christmas. It was your last chance to really indulge before weeks of restraint, which meant people went all out. The combination of end-of-harvest abundance and pre-fast feasting created a perfect storm of celebration.

November 11th also became a significant date for practical economic reasons. This was settlement day—when annual debts were paid, servants received their wages (often including a goose as part of their compensation), and contracts renewed or ended. Shepherds received their “bélesadó” or “rétespénz” (pastry money) from farmers on this day, and in return, they’d present the landowners with multi-branched willow switches called “St. Martin’s rod,” which were kept as symbols of prosperity.

The tradition of going house to house on St. Martin’s Day evolved from these payment customs. Once the actual economic obligations faded from memory or became formalized differently, the door-to-door visits transformed into something more playful—children dressing as beggars (echoing the cloak-sharing legend), reciting verses, and receiving treats. Sound familiar? St. Martin’s Day customs share DNA with both Thanksgiving and Halloween, sitting chronologically between All Saints’ Day and St. Nicholas Day (December 6th), borrowing elements from both.

Geese, Wine, and Weather Prophecy

The saying goes: “He who does not eat goose on St. Martin’s Day will be hungry all year.” This wasn’t just culinary advice—it was survival wisdom dressed up as folk belief. If you hadn’t managed to stock your larder sufficiently by mid-November to afford a goose feast, you were probably facing a lean winter indeed. The goose dinner became both a celebration of successful preparation and a sort of prosperity insurance policy.

Alongside the goose came new wine tasting. Grapes harvested in autumn would have just finished their first fermentation by November, producing young wine that was drinkable but still rough around the edges. St. Martin’s wine became traditional accompaniment to the feast, and in wine-producing regions, the day took on special significance as a celebration of the vintage.

Hungarian folk wisdom also turned St. Martin’s Day into a weather prediction tool. One saying goes: “If Martin arrives on a white horse, expect a mild winter; if on a brown horse, a harsh winter awaits.” Another claims: “If the goose walks on ice on St. Martin’s Day, it will splash in water at Christmas”—meaning if November 11th is cold and icy, Christmas will be mild and rainy. A third tradition held that St. Martin’s Day weather predicts March conditions. After the feast, if rain fell, people expected frost followed by drought.

Even the goose bones supposedly told the future. After carving the bird, families would examine the wishbone from the breast. A long, white bone meant a long, snowy, harsh winter ahead. A short, brown bone promised mild weather. Medieval meteorology at its finest.

Lanterns, Costumes, and Childhood Magic

In German-speaking regions and areas influenced by German culture (including parts of Hungary), St. Martin’s Day became especially focused on children. Kids would craft lanterns from paper, hollowed-out beets, or other materials, light candles inside them, and parade through neighborhoods after dark. Sometimes a man dressed as St. Martin would lead the procession on horseback, recreating the saint’s arrival to share his cloak with the beggar.

The lantern tradition’s exact origins remain mysterious. Some scholars suggest they replaced earlier bonfire customs, symbolically representing the light of holiness piercing darkness, just as Martin’s charity brought hope to the poor. Whatever their origin, lantern walks became magical experiences for children—streets glowing with handmade lights, voices singing traditional songs, the boundary between ordinary evening and enchanted celebration dissolving.

Children would also dress as beggars, reenacting Martin’s encounter with the freezing man at the gates of Amiens. Some would perform short plays telling St. Martin’s stories, then go door to door receiving treats—apples, nuts, small gifts. In some regions, a Krampus-like figure would make appearances, mildly frightening children before rewarding them. Other places featured a bearded, gift-bringing figure on horseback, not unlike an early-winter Santa Claus prototype.

In Hungary, particularly in areas with German-speaking populations, these customs took root and persisted. Hungarian kindergartens and schools often celebrate St. Martin’s Day with lantern-making workshops followed by evening parades. The traditions might have faded in some places, but they’re experiencing revival as communities reclaim historical celebrations.

Budapest’s Modern St. Martin’s Day

Today, St. Martin’s Day in Budapest manifests primarily as a spectacular gastronomic event. November brings “goose days” or “goose weeks” to restaurants across the city, with establishments competing to offer the most tempting goose dishes and new wine pairings. Walking through Budapest in mid-November, you’ll encounter menus featuring roasted goose leg, goose liver, goose soup, and every imaginable variation of preparation.

The tradition extends beyond just eating goose—it’s about communal celebration, seasonal marking, and connecting with historical continuity. When you sit down to a St. Martin’s Day feast in a Budapest restaurant, you’re participating in customs that medieval peasants and nobles alike would recognize, even if the dining room has better lighting and indoor plumbing than they enjoyed.

Family-friendly events also populate the Budapest calendar around November 11th. Lantern-making workshops, children’s parades, storytelling sessions about St. Martin’s life, and market celebrations appear across the city’s districts. These events offer visitors a chance to experience Hungarian folk traditions firsthand, especially meaningful if you’re traveling with children who might enjoy the hands-on, festive atmosphere.

Why It Matters to Visitors

St. Martin’s Day offers something rare in modern tourism: an authentic local celebration that hasn’t been repackaged primarily for visitors. Yes, restaurants advertise their goose menus enthusiastically, and yes, you’re welcome to join the feast. But this isn’t a fabricated “cultural experience”—it’s Hungarians marking a day that’s mattered to their ancestors for over a millennium.

Experiencing St. Martin’s Day in Budapest means tasting history literally. The goose you’re eating connects you to medieval feasts, to agricultural calendars, to folklore about saints hiding in barnyard pens. The new wine you’re sipping comes from the same tradition of celebrating harvest completion. Even the lanterns children carry echo centuries-old customs about bringing light to winter darkness.

It’s also a chance to see Budapest at its most communal and cozy. November isn’t peak tourist season—the weather’s turned chilly, days are short, and the city settles into a more intimate rhythm. St. Martin’s Day breaks up the darkening month with warmth, abundance, and celebration. It’s Budapest reminding itself (and anyone lucky enough to be visiting) that even as winter approaches, there’s still plenty of reason to gather, feast, and be grateful.

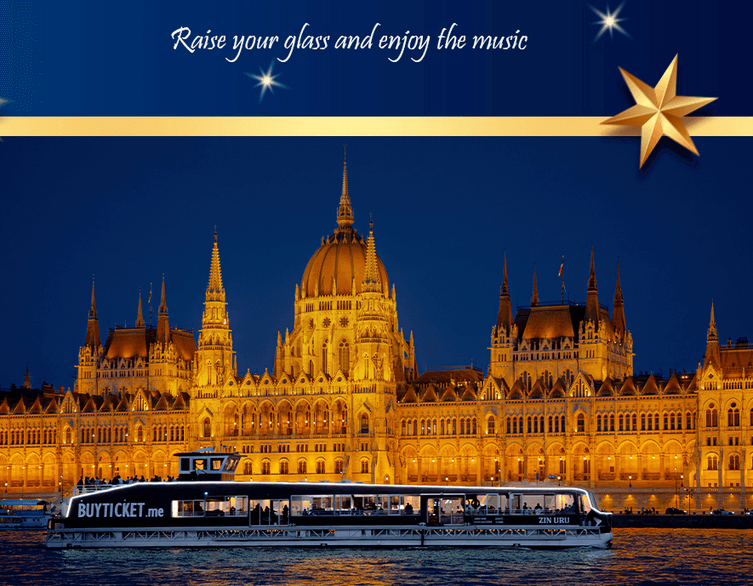

So if you find yourself in Budapest around November 11th, seek out a restaurant serving St. Martin’s Day goose. Raise a glass of new wine. If you hear singing and see a parade of lantern-carrying children, follow them for a bit. You’ll be walking in the footsteps of centuries of celebrants, all honoring a humble saint who once cut his cloak in half for a stranger and couldn’t hide from his calling, even in a goose pen.

Related news