Beaver-Gate: How Budapest’s Railway Almost Lost to Three Furry Engineers

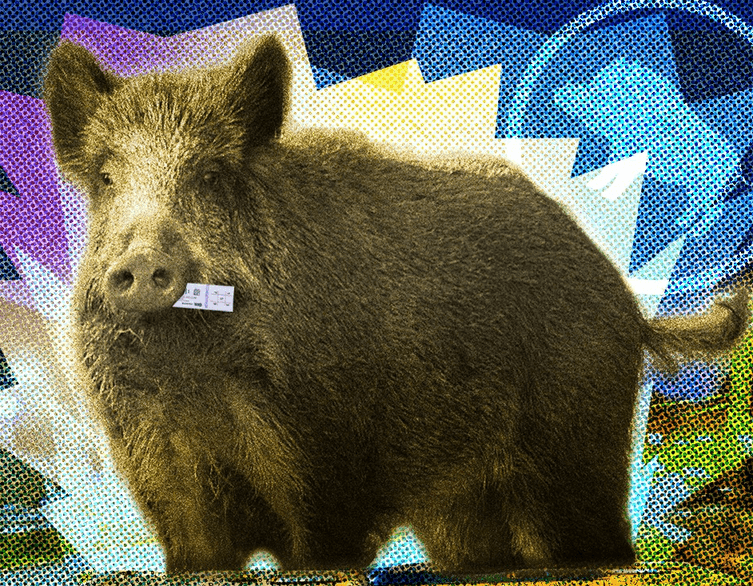

Picture this: a family of beavers decides Budapest’s 15th district looks like prime real estate, moves into Csömöri Creek, and immediately starts building dams with the enthusiasm of property developers who just discovered an undervalued neighborhood. Three dams. Because why stop at one when you’re on a roll? What could possibly go wrong when your ambitious riverside renovation project starts threatening a railway embankment? This is the absolutely bonkers story of how Budapest’s engineers negotiated the most unusual roommate agreement in the city’s history.

The Unauthorized Construction Project

Two years ago, some entrepreneurial beavers decided the Danube was getting too mainstream and swam upstream into Csömöri Creek. They took one look at the secluded valley near Dunakeszi Road and thought “this screams waterfront property development.” Surrounded by abandoned fields, a quarry lake, and a railway embankment, with humans nowhere in sight, it was basically the rodent equivalent of finding a rent-controlled apartment in central Budapest with Parliament views.

Being industrious overachievers, the beavers constructed three magnificent dams without bothering with permits, environmental impact assessments, or informing the neighbors. The creek obediently spread across the valley, creating a nearly two-hectare wetland habitat that would make any landscape architect weep with envy.

The beavers apparently created an Instagram account because frogs, newts, water snakes, and marsh turtles started showing up like it was the hottest new club opening. Fish populations exploded, attracting grey herons who told the egrets, who mentioned it to the mallards, and before you know it, kingfishers were making reservations. Within months, the beavers accidentally created one of Budapest’s newest wildlife hotspots without a single government grant.

Houston, We Have a Problem

Everything seemed perfect until some killjoy engineer noticed the rising groundwater threatening the railway embankment. The water level was endangering the tracks serving the Veresegyház line, which would be deeply inconvenient for thousands of daily commuters who probably don’t appreciate their train derailing because some overzealous rodents got carried away with home improvement.

The knee-jerk reaction would be evicting the beavers to the zoo like unruly tenants. Except this accomplishes nothing—another beaver family would simply swipe right on the same location and rebuild, probably faster and better. Plus, beavers are protected species worth fifty thousand forints each, meaning you can’t evict them without proper permits, environmental assessments, and probably a strongly worded letter from the EU. It’s the bureaucratic equivalent of trying to remove a difficult tenant who knows all their legal rights and has a really good lawyer.

The Slovenian Secret Weapon

Last spring, representatives from the Hungarian State Railways, Budapest’s environmental specialists, the Budapest Sewage Works, and the Pest County Government Office gathered for what was probably the strangest corporate meeting anyone had attended. Their mission: figure out how to keep both the beavers and the railway happy, because apparently 2025 is the year we negotiate with rodents.

Enter Erika Juhász, Hungary’s foremost beaver specialist and the person you want on speed dial when your infrastructure is being held hostage by dam-building aquatic mammals. She recommended a technique tested in Slovenia, where they’ve been managing beaver drama for years like absolute professionals.

Here’s the clever part: if you cut a U-shaped depression in the dam and install flexible pipes running downstream, the backed-up water flows through while the dam stays intact. The pipes set the maximum water height like a thermostat for beaver lakes. From the beavers’ perspective, their dam is still there doing its job. They’re like “look at this cool feature that spontaneously appeared in our construction, neat!”

Best deals of Budapest

The tricky part requires precise calculations. Install the pipes too deep and beavers build another dam upstream, possibly closer to the embankment—solving your flooding problem by creating a worse flooding problem, which doesn’t look great on anyone’s performance review.

Operation: Don’t Tell the Beavers

In October, two industrial divers and three Sewage Works specialists entered the creek while supporters watched from shore like it was the world’s most unusual sporting event. Slovenian beaver expert Martina Vida provided telephone guidance, which is definitely the most niche technical support call anyone’s ever made.

The team installed two six-meter-long pipes inside mesh cages to prevent clogging, which felt like assembling IKEA furniture underwater, in a creek, with beavers potentially watching and judging your technique. The entire operation took three hours and cost roughly one million forints—a bargain compared to the several million forints mechanical dam demolition would cost, money you’d waste completely since beavers typically return and rebuild like they’re on a revenge tour.

The Invisible Architects

Here’s the kicker: despite multiple site visits and three hours of construction work, specialists never encountered a single beaver. The mystery beavers apparently have the social calendar of celebrities who refuse to acknowledge paparazzi, or possibly they were watching from their lodge thinking “what are these weird hairless beavers doing to our dam?”

Nobody knows exactly how many live there—roughly three to eight individuals who apparently work harder than most construction crews despite lacking opposable thumbs. What matters is the incredible value they created. If anyone wanted to construct a similarly large and ecologically rich natural habitat through normal means, it would cost approximately one hundred million forints and require environmental consultants, contractors, and probably five years of planning meetings. The beavers created it for free in less time than it takes most people to renovate their bathrooms.

Plus, fifty meters downstream sit two additional beaver dams because apparently these overachievers believe three dams are better than one. That’s three hectares total that beavers reorganized free of charge like they’re running some kind of environmental charity. The habitat already shows such impressive biodiversity that specialists think it might deserve official nature conservation protection. Imagine telling the beavers their illegal construction project is now a protected heritage site.

The Forgotten Punchline

Juhász adds the perspective that makes this entire saga even more absurd: this three-hectare natural treasure only seems new because we have short memories. Before humans regulated the creek with the confidence of people who definitely know better than nature, this was naturally a water-logged area. The beavers didn’t create anything new—they simply hit “undo” on 150 years of human interference.

Meanwhile, following recent drought-stricken summers, everyone discusses water retention, landscape flooding, and wetland habitat benefits. Politicians make speeches, experts write reports, taxpayer money funds water management studies. Yet rarely does anyone suggest the obvious solution: let the beavers do it. These industrious rodents achieve precisely the desired environmental outcomes automatically, for free, without grant applications or feasibility studies.

Instead of viewing beavers as adversaries in some infrastructure cold war, perhaps it’s time to recognize them as unpaid environmental consultants working toward the same goals Budapest desperately needs. After all, any engineer who works for free, creates hundred-million-forint habitats, improves biodiversity, manages water retention, and only occasionally threatens railway embankments deserves at least a little appreciation—and maybe a thoughtfully installed drainage pipe or two that they’ll probably just incorporate into their next construction project anyway.

The real question is: when do the beavers send Budapest an invoice?

Related news