St. Martin’s Day Around Europe: How a Hungarian Saint United a Continent Through Food, Light, and Generosity

November 11th might not appear on many international calendars as a major holiday, but across Europe, St. Martin’s Day creates a tapestry of celebration that connects Germany to Portugal, Austria to Poland, France to Slovenia. What started as a feast day honoring a 4th-century Roman soldier-turned-bishop has evolved into a beloved tradition that marks the transition from autumn abundance into winter’s approach. While the specifics vary wildly from country to country—some focus on children’s lantern processions, others on wine blessings, and nearly everyone on roasted goose—the spirit remains remarkably consistent: gratitude, generosity, and gathering together before winter’s darkness settles in.

For visitors exploring Europe in November, St. Martin’s Day offers something special: a glimpse into authentic local traditions that haven’t been repackaged primarily for tourists. This is living folklore, celebrations that evolved organically over centuries and continue because communities genuinely value them. Let’s take a journey across the continent to see how different cultures honor the same saint in wonderfully diverse ways.

Germany: Where Lanterns Light Up the Night

If St. Martin’s Day has a spiritual homeland beyond Tours in France, it’s Germany. The German celebration, called Martinstag, transforms into a multi-day event that captures childhood imagination like few other holidays manage. The centerpiece? Lantern processions called Laternelaufen that turn ordinary November evenings into something magical.

In the weeks leading up to November 11th, German schoolchildren craft lanterns in classrooms across the country. These aren’t store-bought plastic affairs—they’re handmade creations involving colored paper, wire, glue, and considerable effort. Some children carve lanterns from hollowed-out beets or turnips, creating the historical predecessor to our modern Halloween jack-o’-lanterns. Others construct elaborate paper designs featuring stars, moons, or abstract patterns that glow when candles flicker inside them.

On St. Martin’s Eve and the night of November 11th itself, these children take to the streets in organized processions. Picture hundreds of glowing lanterns bobbing through the darkness like earthbound constellations, carried by bundled-up kids singing traditional Martin songs. Often, a man dressed as a Roman soldier rides a white horse at the procession’s head, recreating St. Martin’s legendary act of charity. When everyone reaches the town square, a massive bonfire called Martinsfeuer gets lit, and children receive Martin’s pretzels—special twisted breads baked specifically for this occasion.

In the Rhineland region, the celebration extends beyond the procession. Children go door to door with their lanterns, singing songs in exchange for candy, fruit, and sweets—a custom called Martinssingen that strongly resembles Halloween trick-or-treating. The tradition supposedly originated from the medieval practice of going house-to-house collecting food for the St. Martin’s feast, though now it’s evolved into a charming excuse for neighborhoods to interact and children to amass impressive candy collections.

The culinary component centers on Martinsgans—roasted goose served with red cabbage, dumplings, and often roasted chestnuts. Restaurants advertise their Martin’s goose feasts weeks in advance, and families gather for elaborate meals that mark the agricultural year’s end. The goose tradition connects directly to the legend of Martin hiding in a goose pen to avoid becoming bishop, only to be betrayed by the birds’ honking. Germans have been playfully punishing geese for this alleged treachery for over a millennium.

Kempen, near Cologne, hosts Germany’s largest St. Martin’s procession, with up to 8,000 participants following the mounted “St. Martin” through illuminated streets. It’s become a tourist attraction in its own right, drawing visitors from across Europe who want to experience this quintessentially German tradition.

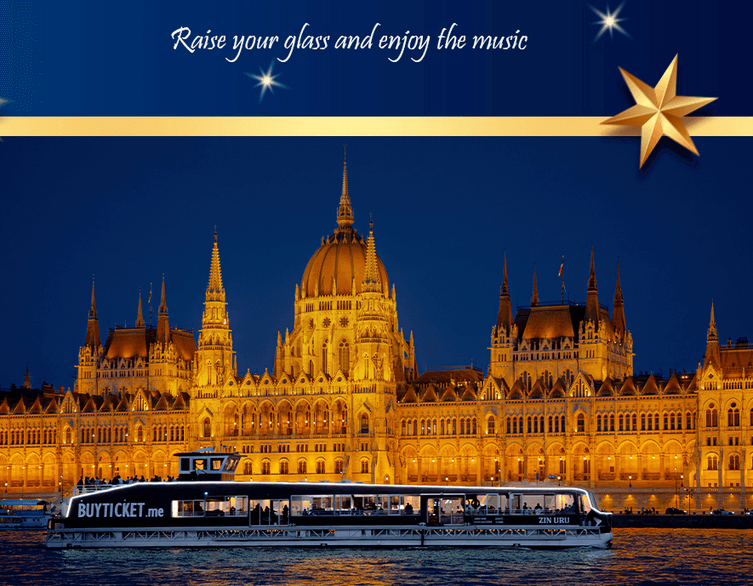

Best deals of Budapest

Austria: Wine, Lanterns, and Seasonal Transitions

Austrian celebrations closely mirror German traditions but add their own distinctive touches, particularly in wine-growing regions. Children participate in lantern processions similar to Germany’s, walking through villages singing Martin songs while their handcrafted lanterns cast dancing shadows on cobblestone streets. The Austrian specialty roasted goose, called Martinigansl, becomes the seasonal obsession, with restaurants competing to offer the most succulent preparations.

Where Austria distinguishes itself is through Martiniloben, a collective festival particularly important in wine-producing areas like Burgenland and Styria. This celebration marks the end of the wine-growers’ year, a moment when vintners can finally assess their harvest and begin enjoying the fruits of their labor. Events include wine tastings where the new vintage gets its first proper evaluation, art exhibitions celebrating local culture, and live music performances that turn the day into a proper community festival.

The tradition of wine christening on St. Martin’s Day carries special significance. According to folklore, “on St. Martin’s Day, must becomes wine”—referring to the grape juice that’s been fermenting since autumn harvest. Wineries hold ceremonies blessing and officially declaring their wine ready, often accompanied by toasts, traditional foods, and considerable merriment. It’s Austria’s version of Beaujolais Nouveau Day, but with deeper historical roots and more seriousness about the wine itself.

November 11th also marks another beginning in German-speaking countries: Carnival season officially starts at exactly 11:11 AM (am elften elften um elf Uhr elf). This launch remains relatively low-key compared to the wild Carnival celebrations that will explode months later, but it adds another layer of festivity to St. Martin’s Day, giving people multiple excuses to gather and celebrate.

France: Honoring Their Hometown Saint

St. Martin of Tours is, obviously, particularly important in Tours, France, where he served as bishop and where his tomb became one of medieval Europe’s most important pilgrimage sites. The French approach to Martinmas tends toward the more religious and contemplative compared to the exuberant German children’s festivals, though regional variations exist.

In Tours itself, St. Martin’s Day involves church services, processions honoring the saint’s relics, and community gatherings that emphasize Martin’s charitable legacy. The focus leans more toward adult participation and religious observance rather than children’s entertainment, reflecting French Catholic traditions.

French wine regions, particularly in areas like Alsace and Lorraine that border Germany, embrace the wine-blessing aspect of the holiday enthusiastically. New wine gets consecrated and tasted, making St. Martin’s Day a significant date on the viticulture calendar. In Alsace specifically, families with young children do participate in lantern traditions borrowed from neighboring German culture, crafting painted paper lanterns and carrying them in nighttime processions up mountainsides—a beautiful fusion of French and German customs in this historically contested border region.

The culinary tradition in France naturally includes roasted goose, though regional variations appear. Some areas prepare duck or other poultry, and coastal regions might feature different proteins entirely. What remains consistent is the feast aspect—gathering for abundant meals that celebrate autumn’s harvest before winter’s scarcity.

Poland: Poznań’s Sweet Twist

Poland celebrates St. Martin’s Day with particular enthusiasm in Poznań, where the holiday has become the city’s signature event. The Polish version, called Święto Marcina, combines religious observation with a uniquely local culinary tradition that sets it apart from other European celebrations.

Yes, Poznań residents eat roasted goose on St. Martin’s Day, maintaining that continental tradition. But the city’s true claim to fame is rogale świętomarcińskie—St. Martin’s croissants. These aren’t French-style butter croissants; they’re horseshoe-shaped pastries filled with white poppy seeds, dried fruits, and nuts, glazed with sugar icing and topped with more nuts. Their creation requires such specific technique and recipe adherence that they’ve earned Protected Geographical Indication status from the European Union.

The story goes that these croissants were inspired by St. Martin’s horse’s hooves, though the historical accuracy of this origin story is questionable. What’s undeniable is that Poznań takes these pastries seriously. Bakeries produce them in massive quantities leading up to November 11th, and the city organizes parades, competitions, and celebrations centered around these sweet treats. It’s a wonderful example of how local culture can adapt a pan-European tradition into something distinctly its own.

Czech Republic and Slovakia: Predicting Winter’s Arrival

Both Czech and Slovak celebrations of St. Martin’s Day closely resemble Hungarian traditions—roasted goose, new wine tasting, and family feasts dominate the observance. The shared history and cultural connections across Central Europe create similar holiday expressions, though each nation adds its particular flavor.

The Czech saying “Svatý Martin přijíždí na bílém koni” (St. Martin arrives on a white horse) refers to the frequent appearance of the first snow around November 11th. This weather lore transforms St. Martin into an unofficial herald of winter, the figure whose arrival signals the definitive end of autumn. Whether the snow actually arrives on schedule or not, the saying captures the seasonal transition that St. Martin’s Day represents—the boundary between harvest abundance and winter preparation.

Both countries maintain strong wine culture, so the new wine tasting aspect receives considerable attention, particularly in wine-producing regions like Moravia in the Czech Republic and southern Slovakia. Wine cellars open their doors for tastings, festivals celebrate the vintage, and the beverage flows as freely as conversation.

Portugal: Chestnuts Instead of Geese

Portuguese celebration of Dia de São Martinho takes a different culinary direction entirely—no goose in sight. Instead, the traditional food pairing involves roasted chestnuts and new wine, particularly água-pé (literally “foot water,” referring to weak wine made by adding water to the grape pressings after the first wine extraction).

The chestnut tradition fits Portugal’s climate and agricultural patterns better than goose farming ever would. On November 11th, Portuguese people gather for magusto celebrations—outdoor parties centered around chestnut roasting, wine drinking, and socializing. The chestnuts roast in perforated pans over open fires, filling the air with their distinctive sweet, smoky aroma. People warm their hands on the hot nuts before peeling and eating them, washing them down with young wine.

The weather saying “No São Martinho vai à adega e prova o vinho” (On St. Martin’s Day, go to the wine cellar and taste the wine) emphasizes the wine component, while another saying notes that St. Martin’s Day often brings a brief warm spell—Verão de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Summer)—a last gasp of pleasant weather before winter truly settles in. It’s Portugal’s equivalent to Indian Summer, that unexpected warmth that makes November momentarily feel like extended autumn.

Slovenia: Baptizing the Wine

Slovenian St. Martin’s Day celebrations, called Martinovanje, focus almost exclusively on wine. According to tradition, must (unfermented grape juice) officially becomes wine on November 11th, requiring a ceremonial “baptism” to mark the transformation. Wineries and wine-growing regions across Slovenia hold elaborate ceremonies where new wine gets blessed, named, and declared ready for consumption.

These aren’t solemn religious services but festive community gatherings featuring music, dancing, traditional foods, and of course, extensive wine sampling. Wine producers welcome visitors to their cellars, offering tastes of the new vintage while explaining the year’s growing conditions and their hopes for how the wine will develop. It’s part agricultural celebration, part cultural festival, and entirely Slovenian in character.

The focus on wine over other traditions makes sense given Slovenia’s strong viticulture heritage. While goose might appear on some tables and churches hold services honoring St. Martin, the wine baptism remains the day’s defining characteristic, transforming November 11th into Slovenia’s most important date on the wine calendar.

Malta: Neighborly Gift-Giving

Maltese celebration of Jum San Martin retains medieval gift-giving traditions that have faded elsewhere. Children receive small cloth bags filled with seasonal fruits, nuts, and sweets—a custom that once had economic significance when St. Martin’s Day marked payment and settlement dates. While the bags no longer represent actual wages or debt settlements, the tradition continues as a charming way to mark the feast day.

The gift-giving aspect, combined with door-to-door visiting customs, gives Maltese St. Martin’s Day a character somewhere between Thanksgiving and an early Christmas celebration. It emphasizes community bonds, generosity, and seasonal marking in a Mediterranean climate where November doesn’t bring the dramatic harvest-to-winter transition that northern European countries experience.

The Common Thread

Despite vast differences in how countries celebrate St. Martin’s Day, certain themes appear universally. The agricultural calendar’s culmination—acknowledging that field work has ended and winter preparation must begin. Wine tasting, recognizing that fermentation has progressed enough to judge the year’s vintage. Generous feasting, particularly involving rich foods like goose that provide calories against approaching cold. Light in darkness, whether through lantern processions or bonfires, symbolizing hope and community against winter’s isolation.

Most fundamentally, St. Martin’s Day celebrates generosity. Martin’s act of cutting his cloak to share with a freezing beggar resonates across cultures and centuries. The holiday’s various expressions—children sharing lantern processions, families gathering for abundant meals, communities opening wine cellars to neighbors, people going door-to-door with gifts—all echo that founding act of seeing someone in need and responding with immediate, practical compassion.

For travelers in Europe during November, seeking out local St. Martin’s Day celebrations offers authentic cultural experiences. Whether you’re watching German children parade with glowing lanterns, tasting new wine at an Austrian Martiniloben, savoring Poznań’s famous croissants, or joining a Portuguese magusto around a chestnut-roasting fire, you’re participating in living traditions that connect you to centuries of European communities marking the seasons, honoring their saints, and finding reasons to gather, feast, and celebrate even as darker, colder days approach.

Related news