Sacred Traditions: Understanding Hungarian, Jewish, Islamic, Mexican, and Tibetan Burial Customs

Death is a universal human experience, yet how different cultures approach it reveals profound differences in worldview, faith, and community values. For travelers visiting Budapest, understanding diverse burial traditions enriches appreciation for the city’s historic cemeteries and the sacred customs they preserve. From the solemn ceremonies of Hungarian funerals to the meticulous rituals of Jewish and Islamic services, the joyful celebrations of Mexican culture, and the sky burials of Tibet, these practices illuminate how humanity honors life’s final passage.

Hungarian Funeral Traditions: Honoring the Departed

Hungarian funeral customs blend ancient beliefs with Catholic traditions, creating ceremonies that balance solemnity with celebration of the deceased’s life. Hungarians traditionally believe the spirit remains near the body for a time after death, and families perform specific rituals to ensure the spirit doesn’t cause harm while also protecting against evil spirits during the funeral procession.

The modern Hungarian funeral ceremony follows a carefully structured process. For traditional casket burials, planning begins with organizing the service, whether religious or civil, selecting music, and choosing wreaths and floral arrangements. The deceased is transported to the funeral home and prepared for viewing. Approximately sixty minutes before the ceremony begins, the body lies in state in the chapel, allowing mourners to gather thirty minutes before the service while contemplative music plays. The farewell speech or ceremony follows, after which the casket is transported to the burial site, lowered into the grave, covered with earth, and adorned with wreaths.

Cremation has become increasingly popular in Hungary due to limited cemetery space. The urn burial ceremony mirrors traditional burial but begins with transportation to the crematorium for cremation. The urn is then placed in the chapel for viewing before the ceremony, followed by placement in an urn wall, urn grave, or columbarium, and wreath laying.

A uniquely Hungarian option involves scattering ashes in designated memorial gardens found at several Budapest cemeteries. The New Public Cemetery features fountain-based water scattering, while Óbuda Cemetery offers water-washing scattering and dry scattering with decorative water elements. Pesterzsébet Cemetery provides dry scattering without water elements, and Csömör Memorial Garden offers dry scattering with decorative water features. These peaceful gardens allow families to say goodbye in natural settings designed specifically for this purpose.

During the wake, relatives and neighbors traditionally visit the body lying in state. Visitors would arrive with specific greetings, look at the deceased’s face, praise their character and deeds, then bid goodnight and depart. Close relatives and elders stay through the night, praying and singing religious songs while men gather separately to compile information for the minister’s farewell speech.

Historical customs reveal fascinating details about Hungarian mourning practices. When carrying the coffin from the house, bearers would knock it three times on the threshold so the dead wouldn’t find their way back. Lamentations, performed only by women through wailing songs, formed an inevitable part of traditional burials despite church prohibitions. These improvised songs mixed reminiscence, leave-taking, and deep emotion.

At the cemetery, mourners participate in the burial by throwing handfuls of soil onto the coffin, and sometimes their tear-soaked handkerchiefs, symbolically leaving their sadness at the graveside rather than carrying it home. Walking around the grave several times remains a common practice at some locations.

The funeral feast traditionally takes place at the deceased’s home, serving bread and bacon or a full meal, typically paprikash meat with bread and wine. A place is always set for the deceased, and mourners share memories. As the gathering continues and emotions soften, they sing the departed’s favorite songs, though when the feast becomes too jovial, an elder relative suggests everyone depart together.

Interestingly, white rather than black was the traditional Hungarian mourning color, representing light. Black mourning dress spread westward from upper classes only in more recent centuries. Some regions continued wearing white mourning clothes well into the twentieth century.

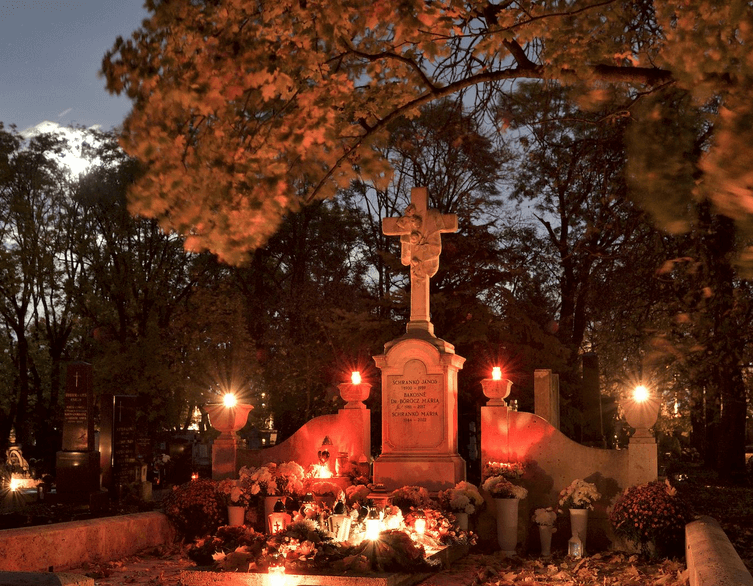

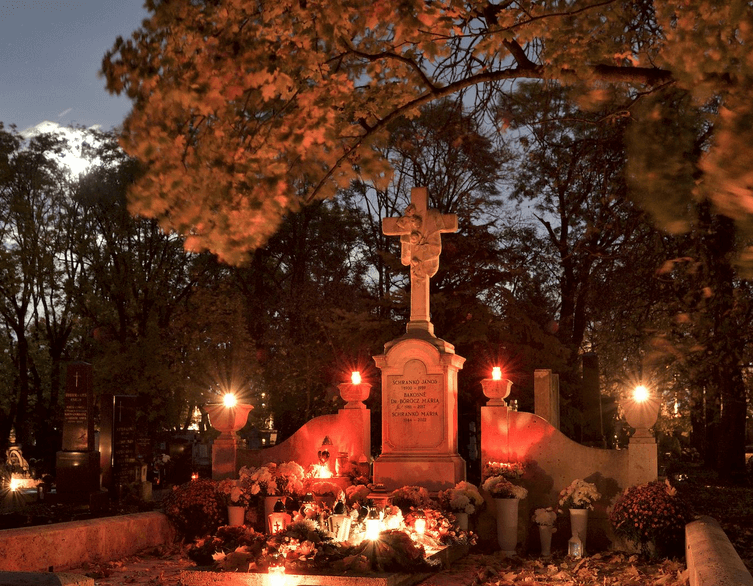

Hungarians observe All Saints’ Day on November first with great devotion, similar to other Catholic cultures. Families attend mass, abstain from work, and bring food like bread and honey-coated scones to the cemetery. On All Souls’ Day, November second, families clean and decorate graves with flowers and candles. Many believe candle flames warm sad souls, while others hold that candles must be lit before souls can return to their graves. Even Protestants participate in these traditions, making the evening of All Saints’ Day a time when living family members, even those far away, return home so the living can meet the dead. These observances remain vital traditions throughout Hungary, in both villages and cities.

Jewish Burial Traditions: Returning to the Earth

Jewish law approaches death with profound reverence, viewing the body as sacred even after the soul departs. According to the Torah, the body must be returned wholly to the earth from which it came, in a form allowing natural decomposition. This fundamental principle prohibits embalming, public viewing of the deceased, cremation, and autopsy except under specific circumstances.

The responsibility for preparing the deceased falls to the Chevra Kadisha, literally the “Holy Society.” This volunteer organization exists in every Jewish community, dedicated to ensuring every Jewish person receives a dignified burial regardless of wealth or status. Members of the Chevra Kadisha ritually cleanse the body and dress it in tachrichim, simple white garments without pockets. This uniform burial attire symbolizes equality before God, where earthly wealth means nothing and divine judgment rests solely on one’s deeds.

For Jewish men, the body is wrapped in a tallit, the prayer shawl worn during life, with one of its fringes deliberately cut. Even those who weren’t observant may be buried in a specially purchased tallit if the family wishes. The coffin itself must be made entirely of wood, with any metal handles attached only with wooden pegs. No interior lining adorns the casket, keeping everything simple and natural.

The funeral occurs as quickly as possible, ideally within twenty-four hours of death. Only fellow Jews should handle the body, carry the coffin, and fill the grave, emphasizing community responsibility. Immediate family members perform keriah, the ritual tearing of garments over the heart, usually at the funeral’s beginning though some communities observe this custom immediately after death or just before the coffin enters the grave. Today, a symbolic scissors cut often suffices.

Traditionally, mourners carried the coffin on their shoulders to the cemetery, with family and community following to honor and comfort the deceased. While modern distances usually prevent this, mourners still accompany the coffin from the chapel to the graveside. Participating in filling the grave represents the final act of love and caring one can perform for the deceased, considered a great mitzvah.

After the burial begins the mourning period, when the community expresses condolences and offers comfort. Those attending the funeral form two parallel lines, and mourners pass between them, embraced by their community’s support.

Islamic Funeral Rites: Swift Return and Sacred Simplicity

In Arabic, the word for death also means peace and stillness. Muslims understand death as the moment when body and soul separate, ending earthly existence and beginning true, eternal life in the hereafter. Islamic tradition teaches against wishing for death even during severe illness or pain. Instead, the dying person should be positioned on their right side facing Mecca, and asked about any outstanding debts or missed fasts, which the community can assume to lighten their burden.

Once death occurs, burial must happen swiftly, preferably the same day, though not during three specific times: sunrise, when the sun reaches its zenith, or sunset, as these times are also prohibited for prayer. Cremation is absolutely forbidden in Islam, as it degrades the deceased. Even a Muslim’s non-Muslim relatives cannot be buried through cremation.

The deceased’s eyes are gently closed, following Prophet Muhammad’s teaching that eyes follow the soul when the angel of death departs with it. The body then undergoes ghusl, the complete ritual washing performed after major impurity, except in this case the living perform it for the dead. Only someone of the same gender may wash the deceased if they were over seven years old, though spouses may wash each other.

Martyrs who die in battle need not be washed, only buried. Though suicide is prohibited in Islam, those who take their own lives still receive washing, prayers, and requests for God’s forgiveness.

Best deals of Budapest

After purification, the body is wrapped in a shroud. The kafan should be white and perfumed, with men wrapped in three layers and women in five. The shrouded body is tied in seven places to secure it, though fewer ties suffice if they hold everything firmly.

At the funeral prayer, the imam stands at the head if the deceased is male, at the middle of the body if female. After prayers, the body is immediately transported to the grave. Women cannot participate in the funeral procession or burial itself. The grave should be approximately person-deep, with the deceased placed on their right side facing the Kaaba in Mecca. Everyone present should participate in filling the grave with at least three handfuls of earth.

The grave’s mound should not exceed one handspan in height, and may be sprinkled with water to help the earth settle. Stones may mark the grave’s boundaries for recognition and protection, but nothing may be built over the grave or written on it, not even names, dates, or Quranic verses. This prevents graves from becoming pilgrimage sites, which could lead to shirk, the gravest sin of associating anything with God. According to the Sunnah, no distinguishing markers should adorn the grave, though a stone at each end is permissible for protection.

Muslims must be buried only in Muslim cemeteries, and non-Muslims only in non-Muslim burial grounds. After the funeral, condolences may be offered anywhere and anytime, with any comforting words appropriate. However, funeral feasts are forbidden. Instead, relatives and neighbors prepare food and send it to the deceased’s family.

Islamic mourning means abandoning ornaments and cosmetics. Women may mourn relatives for three days unless their husbands forbid it. They cannot mourn longer except for deceased husbands, requiring four months and ten days of mourning to reveal any pregnancy. Physical expressions of grief are prohibited: self-harm, shaving hair, or tearing clothes. Islam prescribes no mourning color or special garments.

Visiting graves is permitted solely to remind visitors of death and the Last Day, but bringing flowers or lighting candles at graves is forbidden. Women may also visit burial grounds under these guidelines.

Mexican Day of the Dead: Celebrating Life Beyond Death

Mexican culture’s approach to death stands in stark contrast to most Western traditions. Rather than fearing or avoiding death, Mexicans embrace it, joke about it, and even mock it. This worldview, radically different from European perspectives, creates celebrations where remembering lost loved ones becomes joyful rather than sorrowful.

These traditions trace back to pre-Columbian times. Mayan and Aztec pyramids featured elaborate carvings of skulls and bones, and practiced human sacrifice. Spanish conquistadors killed most indigenous people and converted survivors to a dark, mournful Spanish form of Catholicism that also emphasized death themes. The fusion of these traditions created Mexico’s unique relationship with mortality.

Mexican folk art prominently features death imagery in two forms: one friendly, one fearsome. The friendly version is La Catrina, the grinning, elegantly dressed skeleton woman in a fancy hat appearing everywhere from ice cream shop signs to Diego Rivera murals. These female skeletal figures trace back to the Aztec underworld goddess Mictecacicuatl. Later, in the nineteenth century, the image of a skeleton dressed as a wealthy woman reminded Mexicans that rich and poor alike share the same fate.

The other figure is Santa Muerte, Holy Death. Unlike the friendly Catrina, Santa Muerte carries a scythe and wears a traditional hood, though being Mexico, this hood isn’t necessarily black but might be yellow, red, or even pink. Santa Muerte serves darker purposes as a granter of malevolent wishes, making her less innocent than her hat-wearing counterpart.

The festive atmosphere reaches its peak around the Day of the Dead. On November first and second, Mexicans believe the dead return to earth, and this reunion becomes a cause for celebration. In a way almost incomprehensible to European thinking, this day becomes a joyful popular festival when families build colorful altars in cemeteries beside their loved ones’ graves. These ofrendas feature elaborate cut crepe paper decorations, bouquets and garlands of bright orange cempasúchil flowers, photographs of the deceased, and even their favorite foods and drinks. Tequila inevitably appears, alongside pan de muerto, the “bread of the dead,” an anise-flavored sweet bread bakers make only during these days.

In many places, like Pátzcuaro in Michoacán state, families spend the entire night in the cemetery, not for silent, somber vigil but for celebration. They share funny anecdotes about the deceased, eat and drink beside the grave, and listen to music until dawn.

Mexicans believe death is life’s natural companion, an inevitable part of existence. Rather than mourning someone’s departure, they celebrate that the person lived among them. The deceased themselves supposedly prefer seeing their loved ones happy rather than melancholy. This philosophy transforms grief into gratitude and loss into reunion.

Tibetan Sky Burial: Liberating the Soul

Sky burial represents one of the world’s most distinctive funeral practices. This Tibetan Buddhist ritual involves transporting the deceased to designated mountain sites where the body is offered to vultures. Tibetan Buddhists believe the soul is immortal and death marks a new beginning. Rather than letting the body decay uselessly, they perform a final act of generosity by providing energy to other life forms, freeing the body from the soul and enabling reincarnation.

This practice emerged from the spread of Tibetan Buddhism and its connection with Indian culture. Indian monk Tamba Sanjee brought the tradition to Tibet in the late eleventh century. Every step must strictly follow funeral law.

After death, the body is wrapped in traditional white cloth and placed in a purified corner of the house where the person lived. Custom forbids disturbing the body during this period, as interference disrupts the reincarnation process. The body remains in the house for up to five days while the family invites monks or lamas to read scripture to the deceased, driving out the soul and purifying it from sin.

The family selects an auspicious day for the funeral. On this day, the body is unwrapped and positioned in fetal position, symbolizing rebirth into another world. The body bearer transports the deceased to the burial site, typically located in the mountains far from inhabited areas. Carriers place the body at the site and burn juniper smoke to attract hungry condors and vultures. While birds consume the body, lamas pray.

Several rules ensure the soul’s safe transition. Strangers cannot approach, lest they disturb the process. Even family members must stay away, as their presence might convince the soul to remain rather than journey onward. If vultures immediately rush to the body and quickly devour it, this is the most favorable sign, indicating the deceased has no remaining sins and reincarnation can proceed smoothly. If birds don’t completely consume the body, it suggests the deceased committed serious sins during life, making reincarnation more difficult.

Any remains are burned in the presence of lamas and monks, who bless the spirit with prayers and songs. These chants aim to liberate the soul from the body and cleanse it of all sin.

Understanding Through Travel

For visitors exploring Budapest’s cemeteries, understanding these sacred traditions deepens appreciation for the care and reverence evident in every aspect. The simple wooden markers in Jewish sections, the ornate Hungarian family crypts, the modest graves all reflect profound theological principles about equality, humility, memory, and the body’s return to earth.

These diverse burial customs remind travelers that beneath surface differences lies shared human experience. Whether through Hungarian paprikash shared at funeral feasts, swift Islamic burial, elaborate Mexican celebration, dramatic Tibetan sky burial, or reverent Jewish tradition, every culture seeks to honor the deceased, comfort the living, and affirm beliefs about life’s meaning and what lies beyond.

Walking through Budapest’s historic burial grounds with this knowledge transforms them from mere tourist sites into sacred spaces where universal human experiences of love, loss, faith, and hope have played out across generations. The rituals may differ dramatically, but the fundamental impulse remains constant: to send our loved ones forward with dignity, love, and the fullest expression of our deepest beliefs about existence itself.

Related news