From Communist Monuments to Tourist Attraction: Budapest’s 30-Year Journey to Memento Park

Picture this: you’re strolling through a quiet park in Budapest when suddenly you come face-to-face with towering bronze giants from a bygone era. Welcome to Memento Park, one of Europe’s most unusual tourist attractions, where the ghosts of Hungary’s communist past live on in stone and metal.

When Budapest Said Goodbye to Its Communist Monuments

Over thirty years ago, right around this time in September, something extraordinary happened in Budapest. The city embarked on what locals now call the “great statue removal” – a systematic effort that began on September 14, 1992, to clear socialist-era monuments from public spaces. But here’s the fascinating part: instead of destroying these controversial pieces, Budapest did something unprecedented. They created the world’s first communist statue graveyard.

The timing wasn’t coincidental – the city aimed to remove most of the designated memorials from the streets by October 23rd, Hungary’s national holiday commemorating the 1956 revolution. It was a symbolic gesture, marking the definitive end of the communist era more than three decades ago.

The whole process started two years earlier when the Budapest City Assembly asked districts to nominate which monuments they wanted gone. Out of roughly a thousand public artworks scattered across the city, fifty-eight made the cut for relocation. The city spent 50 million forints on this massive undertaking, treating each statue like a piece of history worth preserving, even if it represented an ideology they’d rather forget.

From Lenin Garden to Memento Park

You might wonder whose brilliant idea this was. The concept actually came from an academic named László Szörényi, who in 1989 proposed creating a “Lenin Garden” where tourists could pay to see communist statues. He was remarkably prescient, predicting that visitors to the planned 1995 World Exhibition would “crowd to see the world’s first Lenin garden” and even “pay in hard currency.”

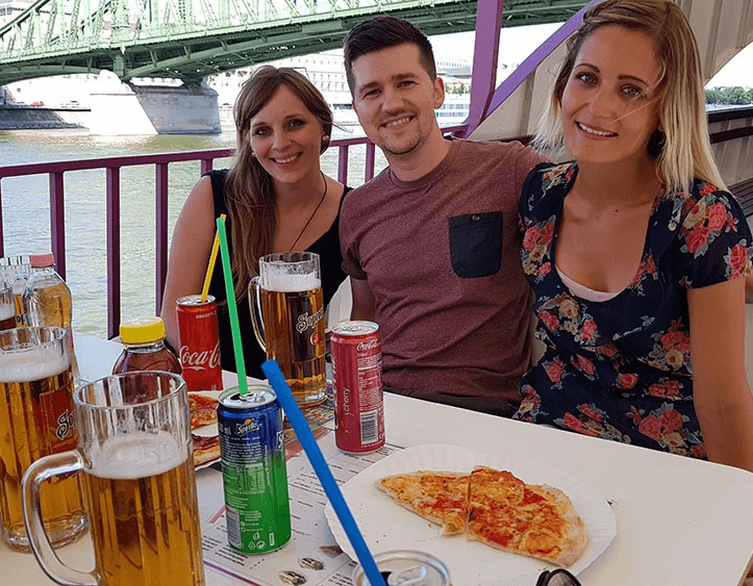

Best deals of Budapest

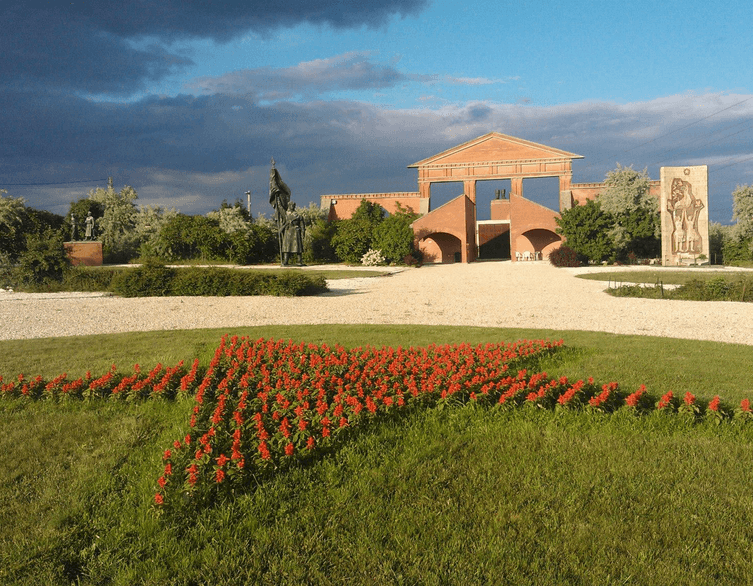

While Szörényi originally had Csepel in mind, the park eventually found its home in Budapest’s 22nd district. Architect Ákos Eleőd won the design competition with a haunting vision that transforms these relics into a powerful meditation on dictatorship and freedom.

Meet the Cast of Communist Characters

Walking through Memento Park today feels like stepping into an open-air history book. You’ll encounter the imposing figures of Marx and Engels, who once dominated Jászai Mari Square right next to the former Communist Party headquarters. These statues by sculptor Segesdi György stirred up quite a controversy when they were removed – protesters actually gathered to sing both the Internationale and the Hungarian national anthem in their defense.

Then there’s Lenin himself, courtesy of sculptor Pátzay Pál. This 1965 creation was the Kádár regime’s attempt to legitimize itself through Soviet symbolism. Art critics might call it “mediocre,” but it perfectly captures the awkward position Hungary found itself in during the Cold War.

But perhaps the park’s most powerful symbol isn’t a full statue at all. It’s just a pair of bronze boots – all that remained after revolutionary crowds toppled Stalin’s massive eight-meter monument on October 23, 1956. The original statue, meant to be “more lasting than bronze,” lasted just five years before becoming one of the most iconic images of liberation in Hungarian history.

The Highway Guardians

Two of the park’s most beloved monuments are the statues of Soviet officers Steinmetz and Osztapenko. For decades, these figures were more than just political symbols – they became genuine Budapest landmarks. Steinmetz greeted travelers heading toward Vecsés, while Osztapenko welcomed generations of families driving to Lake Balaton for summer holidays.

Both officers died on the same day in December 1944 while delivering ultimatums to German forces. Their stories embody the complex relationship between liberation and occupation that defined Hungary’s post-war experience. Locals developed such an attachment to these monuments that their removal sparked genuine debate about whether political art could transcend its original purpose to become part of the city’s identity.

The Controversial Figures

Not every statue in the park represents wartime heroism. Take Béla Kun’s memorial, created in 1986 – ironically, just years before the communist regime collapsed. Kun led Hungary’s brief Soviet Republic in 1919 and was responsible for the Red Terror that claimed hundreds of innocent lives. That he received a monument so late in the communist era speaks volumes about the regime’s desperate attempts to legitimize itself through revolutionary history.

There’s also the “Coat Check Attendant” – locals’ nickname for the dynamic Tanácsköztársaság memorial. This eight-meter figure, appearing to charge forward with a banner, was inspired by a 1919 propaganda poster and occupied the site where a demolished church once stood.

More Than Just a Statue Graveyard

What makes Memento Park special isn’t just what it contains, but how it presents these artifacts. Architect Eleőd designed the entrance as a powerful statement: a triple gate where only the outer doors open, leaving the center permanently sealed behind a steel plate inscribed with lines from Gyula Illyés’ poem “One Sentence on Tyranny.”

As Eleőd explained, “the same silence thunders among the statues as in the verse – pain, mourning, helplessness, shame, astonishment, rage, and defiance.” The park opened on June 27, 1993, marking the second anniversary of Soviet troop withdrawal from Hungary, and has since become one of Budapest’s most thought-provoking attractions.

Why You Should Visit

For foreign tourists, Memento Park offers something you simply can’t find anywhere else in the world. It’s a chance to walk among the physical remnants of Europe’s communist past, preserved not as celebration but as remembrance. The statues, created by some of Hungary’s most talented sculptors, represent significant artistic achievements despite their controversial subjects.

What’s remarkable is how Budapest chose preservation over destruction. Rather than erasing this difficult chapter of history, the city acknowledged it while clearly rejecting its values. This mature approach to confronting the past offers visitors a unique window into Hungary’s journey from dictatorship to democracy.

The park operates as both an outdoor museum and a place of reflection. You’ll find yourself contemplating how authoritarian regimes use public art to project power and shape consciousness. It’s history you can touch, politics made tangible, and ideology frozen in time.

A Living Monument to Freedom

Today’s Memento Park stands as proof that sometimes the best way to reject the past is to preserve it. These statues, which once symbolized oppression, now serve as powerful reminders of freedom’s hard-won victory. They tell the story of a city – and a country – that chose remembrance over forgetting, education over erasure.

Whether you’re a history buff, an art lover, or simply someone curious about one of the 20th century’s most dramatic transformations, Memento Park offers an unforgettable experience. It’s where Budapest keeps its communist ghosts – not buried, but displayed in the full light of day, stripped of their power but not their significance.

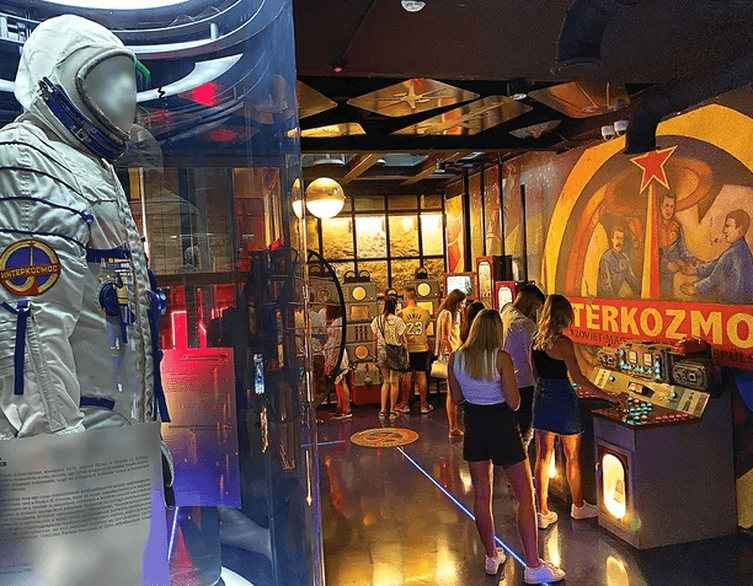

Related attractions