Every Goose Dish Worth Standing in Line For: Budapest’s St. Martin’s Day Feast Guide

There’s a Hungarian saying that goes: “He who does not eat goose on St. Martin’s Day will be hungry all year.” Now, we’re not superstitious or anything, but why risk it? Especially when the risk involves missing out on some of the most spectacularly delicious goose dishes Budapest has to offer every November. St. Martin’s Day on November 11th transforms the city into one giant goose-worshipping food festival, and honestly, if you’re visiting Budapest during this time, you’re about to experience Hungarian cuisine at its most unapologetically indulgent.

Let’s get one thing straight: goose isn’t exactly everyday eating. It’s rich, fatty, and requires commitment from both the cook and the diner. But that’s precisely why St. Martin’s Day exists—to give everyone permission, nay, a cultural obligation, to go absolutely wild with goose for at least one day (or week, or entire month if you’re the restaurants of Budapest) each year. From traditional preparations that would make your Hungarian grandmother nod approvingly to modern fusion dishes that make her do a confused double-take, Budapest’s chefs are pulling out all the stops.

The Classic That Started It All: Traditional Roasted Goose

Let’s begin where every St. Martin’s Day feast should begin—with proper, traditional roasted goose. This isn’t just any roasted bird situation. Hungarian roasted goose is a production, a culinary event that fills your kitchen with aromas so heavenly your neighbors will start inventing excuses to drop by. The goose gets seasoned simply with salt, pepper, and maybe some marjoram, then roasted slowly until the skin achieves that impossible balance of crispy crackle and burnished gold while the meat stays impossibly juicy underneath.

The traditional accompaniments matter just as much as the bird itself. You’ll typically find roasted goose served with braised red or purple cabbage, which cuts through the richness with its sweet-sour tang, and potato dumplings that soak up all those gorgeous pan juices like edible sponges. Some versions add roasted chestnuts or prunes to the mix, adding sweetness that plays beautifully against the savory meat. This is the dish that makes you understand why Hungarians have been celebrating St. Martin’s Day for over a thousand years—when food tastes this good, you invent holidays around it.

Rosemary Roasted Goose Leg: Herbaceous Heaven

If you want something slightly more refined but still deeply traditional, seek out rosemary roasted goose leg. This preparation takes patience—we’re talking hours of slow roasting—but that first bite justifies every minute spent waiting. The rosemary infuses into the meat as it cooks, creating layers of flavor that make each bite interesting. The skin becomes almost impossibly crispy, shattering at the touch of your fork, while the meat underneath achieves that fall-off-the-bone tenderness that separates good roasted meat from transcendent roasted meat.

This dish exemplifies Hungarian cooking philosophy: use quality ingredients, don’t overcomplicate things, and give everything enough time to reach its full potential. It’s the kind of once-a-year indulgence that reminds you why seasonal eating and anticipation make food taste even better.

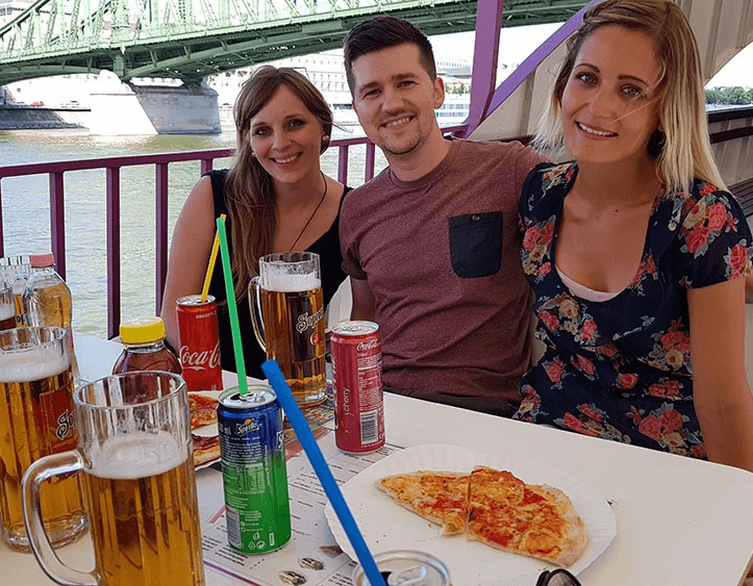

Best deals of Budapest

Ludaskása: Goose With More Goose

Now we’re getting into truly Hungarian territory. Ludaskása translates roughly to “goose porridge,” which sounds deeply unappetizing in English but is actually one of the most beloved traditional dishes associated with St. Martin’s Day. This is a hearty, one-pot meal made with barley or pearl barley, chunks of tender goose meat, vegetables, and goose fat. So much goose fat. It’s creamy, rich, intensely savory, and the kind of stick-to-your-ribs sustenance that carried Hungarian farmers through harsh winters.

Making ludaskása properly means using every part of the goose—neck, giblets, wings—nothing goes to waste. The grains cook slowly in goose stock until they’re creamy and tender, absorbing all those deep, meaty flavors. It’s peasant food elevated to celebratory status, the culinary equivalent of a warm hug from your ancestors. Budapest restaurants serving authentic ludaskása are doing you a service—this isn’t a dish you can easily make in a hotel room.

Goose Neck Soup: Don’t Knock It Till You’ve Tried It

Goose neck soup with tiny dumplings might sound like something you’d politely decline, but hear me out. This soup represents Hungarian resourcefulness at its finest—using parts of the bird that might otherwise go to waste to create something genuinely delicious. The neck gets simmered with vegetables and aromatics until the broth turns golden and rich, then strained and served with tiny flour dumplings called galuska that bob in the liquid like delicious little pillows.

This soup often serves as the opening act to a larger St. Martin’s Day feast, preparing your palate for the heavier courses to come. It’s comforting, warming, and sets exactly the right tone for an evening of indulgence. Plus, starting your meal with soup gives you the moral high ground when you go back for thirds of the main course.

Goose Liver: Hungary’s Not-So-Secret Weapon

Let’s talk about goose liver, because Hungary doesn’t mess around when it comes to this delicacy. You’ll find it prepared multiple ways during St. Martin’s season, each showcasing different aspects of this luxurious ingredient. Seared goose liver appears on elegant restaurant menus, the slices achieving a perfect crust while staying buttery-soft inside. Goose liver pâté—smooth, rich, and often enhanced with Port wine or brandy—gets spread on toast points as an appetizer that makes you reconsider your relationship with spreadable foods.

Some preparations add dried cranberries or blueberries to the pâté, introducing tart fruit notes that balance the liver’s richness. Others keep it simple, letting the ingredient speak for itself with just a touch of alcohol and seasoning. Either way, if you’ve only experienced the mass-produced stuff, Hungarian goose liver during St. Martin’s season will redefine your understanding of what this ingredient can be.

Stuffed Goose Neck: Because Why Not Use Everything?

Stuffed goose neck takes the “use every part” philosophy to its logical conclusion and somehow makes it elegant. The neck skin gets turned inside out, stuffed with a mixture that might include liver, rice, onions, and spices, then sewn shut and cooked until the filling sets and the skin becomes tender. Sliced, it looks almost like a terrine, with the filling creating an attractive pattern against the golden skin.

Served with braised cabbage and parsnip purée, this dish represents traditional Hungarian cooking’s ability to transform seemingly humble ingredients into something special-occasion worthy. It’s the kind of preparation that impresses dinner guests while also honoring agricultural traditions of waste-not-want-not eating.

Székely-Style Goose Leg: Cabbage Gets Its Moment

The Székely-style preparation brings goose together with one of Hungary’s favorite vegetables: sauerkraut. This dish layers tender goose leg over tangy, slow-cooked cabbage seasoned with paprika and sour cream, creating a harmony of rich meat and sharp fermented vegetables that somehow works perfectly. The sauerkraut cuts through the goose’s fattiness like a flavor machete, while the meat’s richness mellows the cabbage’s aggressive tartness.

Served with fresh bread for soaking up the sauce (Hungarians call this “tunkolás”—the art of sauce-mopping), this represents comfort food elevated to festive status. It’s the kind of dish that makes you understand why Central European cuisine revolves so heavily around cabbage—when prepared right, it’s spectacular.

Pulled Goose Burger: Tradition Meets Street Food

Here’s where modern Budapest chefs get creative. November is goose month, so why not transform that traditional meat into something contemporary? The pulled goose burger takes slow-cooked, shredded goose meat—tender, rich, and intensely flavorful—and piles it onto a bun with clever accompaniments that balance the richness. Maybe some pickled vegetables for acidity, perhaps a smear of goose liver pâté for extra indulgence, definitely some crispy onions for textural contrast.

This isn’t your grandfather’s St. Martin’s Day feast, but it’s undeniably delicious and shows how Hungarian food culture keeps evolving while respecting its roots. Plus, eating goose in burger form feels slightly less intimidating than tackling a whole roasted leg, making it a good entry point for goose-curious visitors.

Rosé Goose Breast: Pink Perfection

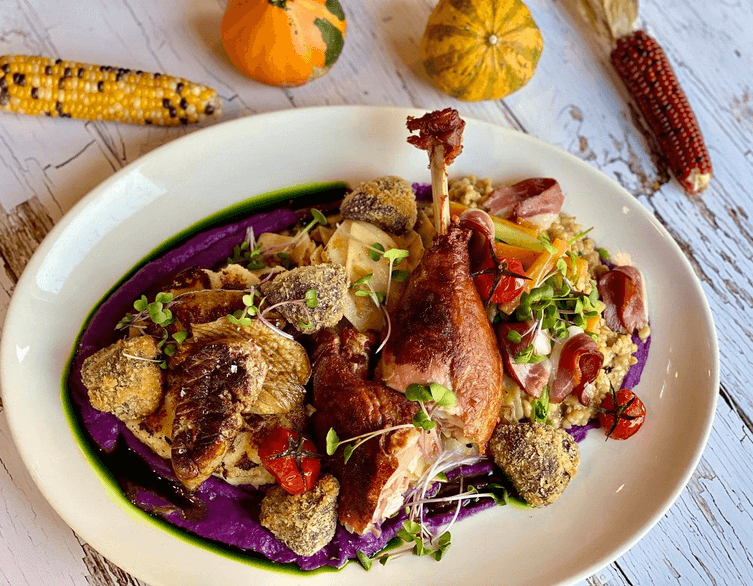

For those who find traditional roasted goose a bit too heavy, rosé goose breast offers a lighter (relatively speaking) alternative. The breast gets cooked to perfect medium-rare, sliced thin to reveal that rosy interior, and served with accompaniments that tend toward the elegant—perhaps beetroot-stained potato purée and honey-roasted fennel, or grape-studded purple cabbage and ginger-spiced sweet potato mash.

This preparation showcases goose breast’s surprisingly delicate side. When not cooked to oblivion, goose breast has a texture closer to duck than to the leg meat, with less fat and a more refined flavor. Served with thoughtful sides and maybe a reduction sauce, it becomes a dish that wouldn’t look out of place at a Michelin-starred restaurant, proving that St. Martin’s Day eating has room for both rustic tradition and refined modernity.

Goose Liver Risotto with Roasted Pumpkin: Autumn on a Plate

This dish perfectly captures autumn’s essence while respecting St. Martin’s Day traditions. Creamy risotto gets enriched with goose liver and studded with roasted pumpkin pieces, sometimes with chestnuts thrown in for good measure. It’s not exactly a conventional St. Martin’s preparation—risotto being distinctly Italian—but it represents how Budapest’s food scene blends Hungarian ingredients with international techniques.

The combination works spectacularly: the risotto’s creaminess provides a luxurious base, the pumpkin adds sweetness and seasonal appropriateness, and the goose liver throughout creates pockets of rich, melting indulgence. It’s the kind of fusion dish that respects both traditions while creating something new and exciting.

Where the Goose Gets Its Glory

Budapest restaurants go all-in for St. Martin’s season, extending goose offerings well beyond November 11th itself. You’ll find “Goose Days” or “Goose Weeks” throughout the month, with establishments competing to offer the most tempting menus. From elegant fine-dining venues serving multi-course goose tasting menus paired with Hungarian wines, to cozy neighborhood bistros offering hearty traditional preparations, to modern street food spots reimagining goose for the grab-and-go crowd, the city becomes a goose-lover’s paradise.

The tradition has evolved from rural agricultural feast to urban culinary event, but the heart remains the same: celebrating abundance, marking the season’s change, and giving yourself permission to indulge in rich, soul-satisfying food. When you sit down to a St. Martin’s Day goose feast in Budapest—whether you choose the ultra-traditional route or opt for something more contemporary—you’re participating in a tradition that connects you to centuries of Hungarian celebrants who understood that sometimes, the best response to approaching winter is to gather around a table, raise a glass of new wine, and feast like the goose depends on it.

Because according to tradition, if you don’t eat goose on St. Martin’s Day, you’ll be hungry all year. And really, why risk it?

Related news