Budapest’s Bold Experiment: Designing a City That Works for Women Too

Budapest’s District II is embarking on something that might sound revolutionary but shouldn’t be – they’re asking women what they actually need from their city. In a world where roughly half of urban residents are women, yet their voices have historically been whisper-quiet in urban planning discussions, this Hungarian district is turning up the volume and listening carefully.

The Great Gender Gap in City Planning

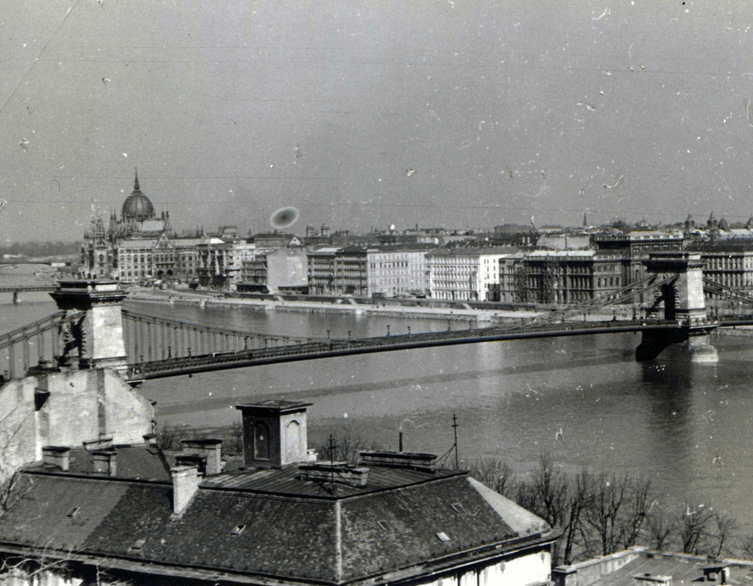

For centuries, cities have been designed primarily by men, for men, with women’s needs often treated as an afterthought or completely overlooked. This isn’t about pointing fingers or assigning blame – it’s about recognizing a fundamental oversight that affects how millions of people experience their daily lives. When you walk through Budapest’s streets, ride its trams, or navigate its neighborhoods, you’re moving through spaces that were largely conceived without considering how women specifically use and experience urban environments.

The statistics tell a compelling story that might surprise many visitors to Budapest. Research conducted by the Budapest Transport Center reveals that women rely on public transportation 16% more than men for longer journeys. They make 57% more trips related to childcare responsibilities and nearly double the number of shopping-related journeys compared to their male counterparts. These aren’t just numbers – they represent real people navigating real challenges in a city that wasn’t necessarily designed with their patterns of movement in mind.

When Everyday Life Meets Urban Reality

Picture a typical day for many women in Budapest: dropping children at school, catching public transport to work, making a quick grocery stop during lunch, picking up children after work, and perhaps squeezing in another errand before heading home. This pattern, known as “trip chaining,” creates a complex web of movement through the city that differs significantly from the more linear commuting patterns that traditional urban planning often assumes.

This difference became starkly apparent to many women during major life changes. As one architect noted, she never really thought about urban accessibility until she had a child and suddenly realized how challenging it can be to navigate Budapest with a stroller. Simple tasks like crossing busy intersections, boarding trams, or finding accessible routes become daily obstacles when you’re pushing a pram through a city designed primarily with the unencumbered pedestrian in mind.

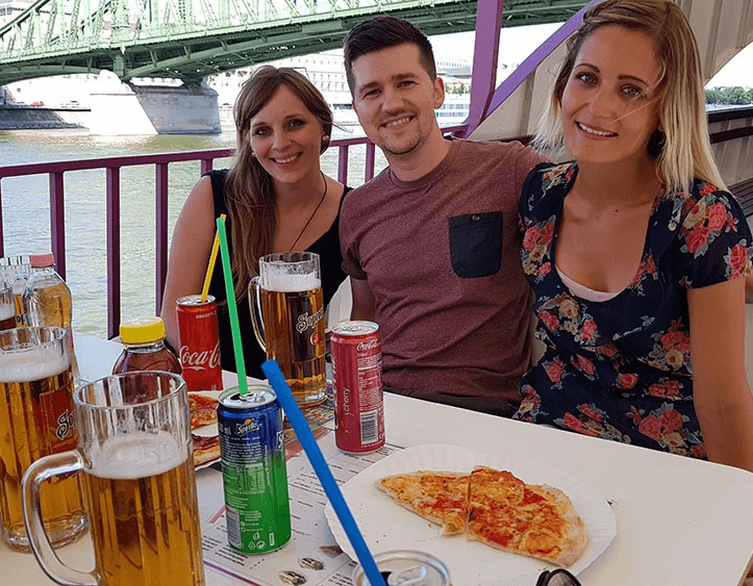

Best deals of Budapest

The Safety Question That Shapes Every Journey

Safety considerations play a dramatically different role in how women and men experience Budapest’s urban landscape. While men often worry primarily about theft when walking at night, women face the additional layer of concern about harassment and assault. This fear isn’t unfounded paranoia – it’s a rational response to real risks that significantly influence how women move through the city.

The quality and extent of street lighting becomes a crucial factor in route planning for many women. Areas that might be perfectly acceptable thoroughfares during daylight hours can feel threatening after dark, leading to longer, more circuitous routes to reach the same destinations. This has a ripple effect on everything from public transport usage to which neighborhoods feel accessible and welcoming.

Learning from Vienna’s Gender-Conscious Approach

Vienna provides an inspiring example of what’s possible when cities actively consider gender in their planning processes. Since the early 2000s, the Austrian capital has operated a dedicated gender unit focused on ensuring city services serve all residents more equitably. This isn’t about grand gestures – it’s about thoughtful details that make a real difference.

One seemingly small but significant example involves public transport handholds. Recognizing that men and women differ in average height by approximately 10 centimeters, Vienna’s transport system includes lower-positioned handholds to accommodate shorter passengers. It’s a simple solution that demonstrates how considering diverse user needs can lead to more inclusive design.

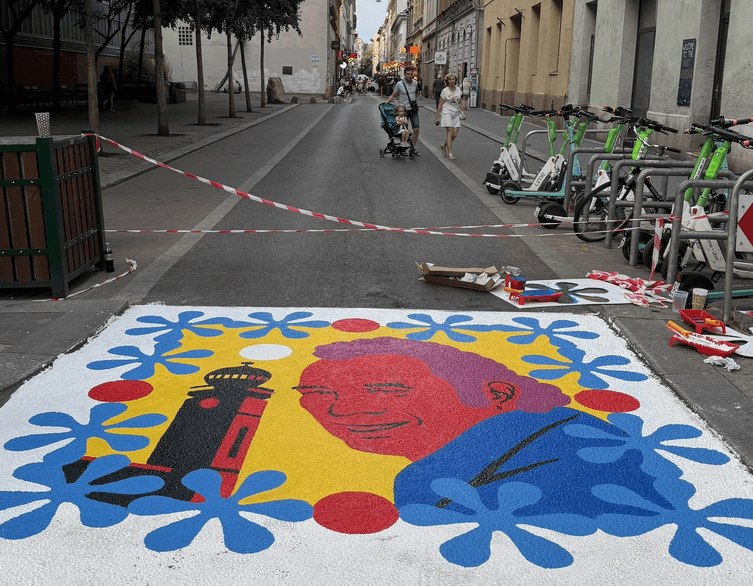

Vienna’s approach began in 1991 with a photography exhibition titled “Who Owns Public Space? – Women’s Daily Lives in the City.” The images documented how different women navigated urban spaces, revealing that regardless of their backgrounds, their movement patterns were primarily determined by where they felt safe and where they encountered the fewest physical barriers.

District II’s Community Conversation Experiment

Now Budapest’s District II is launching its own version of this inclusive approach. In mid-September, they’ll bring together 50 randomly selected women for a five-day community consultation. The goal isn’t to create a separate “women’s agenda” but to ensure that diverse perspectives and experiences inform decisions that affect everyone in the district.

The selection process aims to reflect the area’s demographic diversity, ensuring that women from different age groups, backgrounds, and life situations can contribute their insights. Importantly, no special expertise is required – the organizers emphasize that every life experience brings valuable perspective to urban planning discussions.

The Ripple Effects of Inclusive Design

When cities design with women’s needs in mind, the benefits extend far beyond gender lines. Better lighting improves safety for everyone. More accessible public transport helps parents, elderly residents, and people with mobility challenges. Improved pedestrian infrastructure benefits all walkers, regardless of gender.

Research from the Budapest Transport Center confirms that women are more likely to walk and use public transportation, while men more frequently choose cycling or driving. Understanding these patterns helps planners create transportation networks that truly serve the city’s diverse population rather than defaulting to solutions that work primarily for one demographic group.

Small Changes, Big Impact

Some of the most effective urban improvements are surprisingly modest. Better street lighting, more frequent and accessible public restrooms, improved sight lines at bus stops, and barrier-free access to public transport can dramatically improve urban experiences for many residents and visitors.

The challenge isn’t necessarily about massive infrastructure overhauls – it’s about shifting perspective to consider how different people use urban spaces. When planners ask questions like “How does this intersection work for someone pushing a stroller?” or “Would this route feel safe for a woman walking alone in the evening?” they often discover simple modifications that make spaces more welcoming for everyone.

What This Means for Budapest’s Future

District II’s initiative represents more than just a local experiment in participatory planning. It’s part of a growing recognition across Europe that cities work best when they’re designed with their full population in mind. As Budapest continues to attract international visitors and residents, creating more inclusive urban environments becomes both a matter of social equity and practical competitiveness.

For tourists visiting Budapest, these conversations and eventual changes could mean more accessible attractions, better-lit walking routes between popular destinations, and public transport that’s easier to navigate with luggage or mobility aids. The principles of inclusive design benefit everyone, not just the specific groups they initially aim to serve.

Beyond Gender to Universal Design

While District II’s focus is specifically on women’s perspectives, the underlying principle applies more broadly. Cities that work well for diverse users – whether that’s defined by gender, age, physical ability, or socioeconomic status – tend to be more livable for everyone. The conversations happening in Budapest reflect a broader shift toward urban planning that considers the full spectrum of how people actually live and move through cities.

As this community consultation process unfolds, it will be interesting to see which insights emerge and how they translate into concrete changes in Budapest’s urban landscape. The success of this experiment could inspire other districts and cities to similarly broaden their planning perspectives, creating ripple effects that extend far beyond the borders of District II.

The ultimate goal isn’t to create a city designed specifically for women, but rather a city that works effectively for all its residents and visitors – a vision that benefits everyone who calls Budapest home or comes to experience its unique urban character.

Related news